Exit Interview: Veteran Inquirer Reporter and Editor Bill Marimow

The two-time Pulitzer winner, who’s leaving the paper at the end of the year, on being fired multiple times and the MOVE story he wishes he'd written.

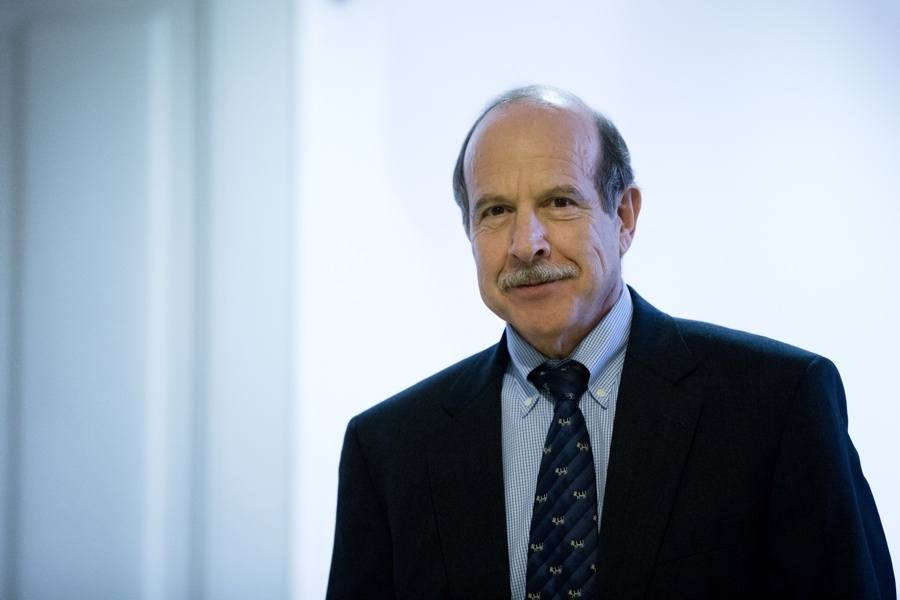

Former Inquirer editor Bill Marimow is stepping away from the paper at the end of this year — this time voluntarily. Photo by Matt Rourke/AP.

If you’ve been a subscriber to the Philadelphia Inquirer at any point over the last five decades, you’ve likely encountered the name Bill Marimow. Now vice president of strategic development at the paper, Marimow began his career at the Inky in 1972 covering labor. He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1978 and 1985 for his work uncovering police brutality, and eventually ascended to the position of top editor. Those who follow local newspaper palace intrigue will remember Marimow’s multiple firings in the 2010s. But Marimow kept coming back.

At the end of this year, Marimow is leaving the paper for good — only this time, it’s of his own volition. (He says he’ll still show up from time to time on the paper’s op-ed page.) At the Inky offices last Friday, we caught up with the veteran journalist to discuss his career at the paper, the one story he never got the chance to write, and what’s next.

You’ve worked at the Inquirer as a writer and editor, and then for the past couple of years on the business side. Which role suits you most?

If I think of myself and what I do best it’s reporting, writing.

Some writers don’t ever want to touch the other side. What made you get into editing?

There are always watersheds in people’s careers. I was a reporter and writer from 1969 to about 1986. What happened in 1985 was the Inquirer went on strike for 45 days. It gave me time to reflect, gave me time to understand where I was in the constellation of reporters and writers. And I realized that many people on the staff were coming to me for advice on how to report a story, write a story, and organize a story.

Back in the ’80s, it was a larger constellation than it is now. Are you nostalgic for the glory days?

Even though I cherish the past, I’ve never been nostalgic. I’m someone who I think is a pragmatist with high ideals. And my view is that even though there are fewer people now, the goal is to do whatever we do with excellence.

You won your two Pulitzer Prizes in the ’70s and ’80s for investigative reporting. Did investigative stories, when they landed after months and months of work, have more impact then by virtue of the slower news cycle?

My belief is that it’s not the speed at which we do the work, it’s the depth, breadth and quality of the work. So for instance, this year, the Inquirer’s had some stories which have landed with a huge impact. An excellent example was Lisa Gartner’s stories about the beatings of young men at Glen Mills. The story broke, and within a few weeks Glen Mills had been closed down, people were being taken out of the school.

Don’t you think, though, that in some cases there are quality stories that seem to disappear now? The one that comes to mind is the Times investigation of Trump’s taxes. That piece came out about a year ago and just fizzled away.

I think there’s a real difference in terms of the subject of Donald Trump and the subject of his presidency and his business. I understand your position, but right now there’s a case in New York City, which my daughter Ann has been covering for the Washington Post, in which the district attorney is fighting to get those taxes. There have been so many investigative stories with an impact about Donald Trump that sometimes the results are months or years away. But the taxes are getting attention.

You’ve covered the news in Philadelphia in five different decades. Have the issues of the day changed between now and then?

I think, to a certain extent, white-collar corruption is not as blatant. … But some of the issues, like police violence, civil rights cases, they continue to be issues that require action by public officials.

Is there a story you wish you had gotten the chance to write but never did?

I would love to have known precisely what happened in the back alley of the MOVE house on May 13th and May 14th in 1985. Based on my reporting, it’s clear that when the fire was put out, many of the MOVE members were dead in the house, burned to death or shot to death. I interviewed many firefighters who were not in the shootout but were in homes looking out at the back alley of the MOVE house, and they talked about people leaving the house. It never made sense to me that people would leave a burning house and then go back in to die. So what happened out there? I don’t know the answer.

I’ve got to bring this up at least once. You’ve been let go by different management —

Fired. Fired is the word.

You’ve been fired by management multiple times. Some people might turn their back on the institution eventually. Why keep coming back?

Well, first of all, make sure you use the word “fired.” Not “let go.” When I was fired the first time, it was a result of the hedge funds taking over after Brian Tierney’s group went bankrupt. When I returned in the spring of 2012, the people who purchased the company were Gerry Lenfest, whom I admired, Lewis Katz, whom I admired, and George Norcross, whom I didn’t know. Given the ownership, I felt very confident that I’d be returning to an Inquirer that was more akin to the Inquirer I liked and respected. When I was fired in October 2013, the person who fired me was Bob Hall, the publisher. I believe, but I can’t prove, that he did it at the behest of Mr. Norcross.

Almost instantaneously, Lewis Katz and Gerry Lenfest filed a lawsuit to get me reinstated. So I came back, with the belief and hope that when all was said and done, Lewis Katz and Gerry Lenfest would be the owners. I believe their commitment to good journalism was comparable to the best publishers in America.

What made you step aside this time?

Two factors. Number one, I’m 72 years old. I’ve been doing orientation for every new employee — business side and journalism side — and almost everyone is young enough to be my child, and in a few cases, young enough to be my grandchild. I’ve got six grandchildren, three in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and three in Washington, D.C. They’re ages two to 12. I’d like to get to know them, and I’d like them to get to know me.

Now that you’ve spent some time on the business side of the operation, what makes you optimistic, if you are, about the continued strength of the Inquirer?

The fact that we’re owned by the Lenfest Institute and that we’re a public benefit corporation. As a public benefit corporation, our goals are doing great journalism and being a viable business. The difference between being a viable business and maximizing your earnings is enormous. So if our profit margins are 2 percent and we’re earning money, that’s okay. Our real obligation is to the public, in contrast to the New York Times, whose obligation is to their shareholders. McClatchy, Gannett — all of them have an obligation to maximize their profits. We have an obligation to be profitable.

I hear you may still be making appearances from time to time in the paper as an op-ed writer. Do you have any ideas that you’re kicking around?

The subjects I would like to write about include the First Amendment, investigative reporting, education. And then I’ve written a few personal essays in the last year. One topic I’ve been thinking about is how I transformed into a subway denizen. I was a major subway and trolley rider for years from West Philly, but more recently I’ve been a walker and a driver. But lately, the driving is so frustrating that I’ve reverted to SEPTA. I’m actually enjoying it.