A Man in Full: D. Herbert Lipson

Philly Mag writers and editors look back on the life of the father of the city magazine.

Herb Lipson was, among many other things, a magazine man. He loved reading magazines, he loved owning them, and he loved pushing the writers and editors who worked for him to create the best ones possible — magazines that took chances and had balls and stirred up trouble while simultaneously being sophisticated and upscale and showing the finer side of life. (Yes, pulling off this trick is as difficult as it sounds.) In the tributes below, a group of writers and editors who’ve been part of Philly Mag for six decades look back on a man who was easy to love, easy to loathe, and impossible to ignore.

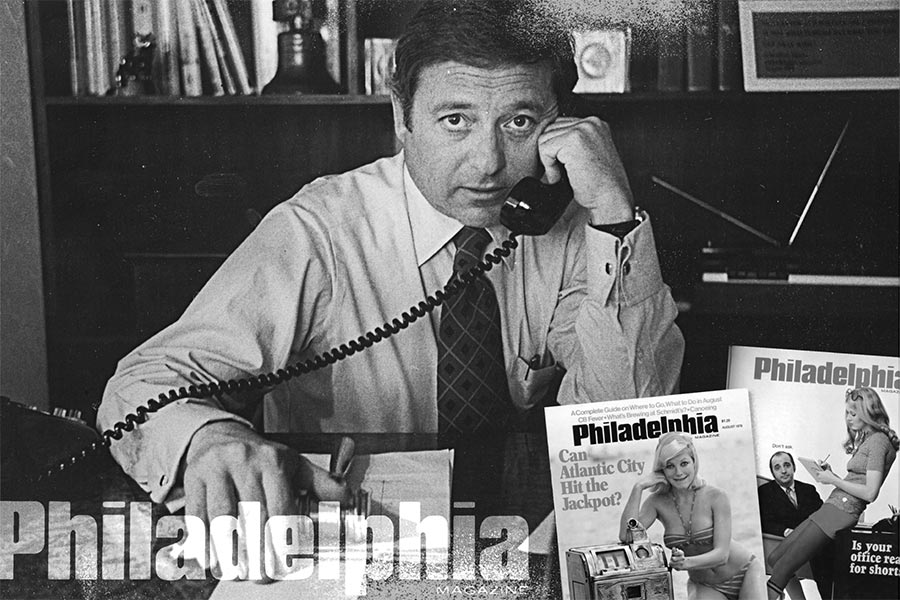

The Publisher

After success with Philadelphia, Herb bought Boston magazine in 1971 and launched Manhattan Inc. in 1984.

For those dwindling few of us who were in on the ground floor of Philadelphia magazine’s explosive development in the 1960s, there is near-universal agreement that the longtime editor, Alan Halpern, deserves most of the credit for inventing a media form that has been copied all over the country. There is, however, one exception, or was until his death five years ago. And no one is entitled to an opinion more than Gaeton Fonzi, who wrote many of the stories that propelled what was known as Greater Philadelphia Magazine from an obscure Chamber of Commerce puff sheet to recognition by such influential publications as Time magazine and the New York Times.

Shortly before his death, Fonzi completed a piece for The Philadelphia Magazine Story, our book about that landmark era. Fonzi, who was with the magazine from 1959 to 1972, was in a unique position to give Herb Lipson the credit he was due. Although he had great respect and affection for Alan Halpern, Fonzi came aboard early enough to witness Herb’s transition from an ad salesman to publisher:

“When Herb Lipson took over as publisher from his father, he did not take his new position as a challenge to keep Chamber members quiet and content. Tooling around in a Mercedes and enjoying the good life with his contemporaries, young Lipson might have come off as a playboy. … But he was a lot more than that. He was affable and soft-spoken but took his new role very seriously. He had a vision of Philadelphia magazine as a new journalism force in the community.”

Lipson recognized that a downtown business audience was interested in what today we call “service” features. Fonzi wrote: “They wanted to know where the action was, the hottest clubs, the best restaurants. Herb Lipson often considered himself the advance scouting party in probing Philadelphia’s new frontier.” Fonzi also recalled that Lipson wanted the magazine to be noticed, suggesting an in-depth investigative piece “that would make Philadelphia ‘an overnight sensation.’”

The subject was Locust Street, at least that Center City portion of it that had garnered the appellation “Lurid Locust Street.” The description of a “gaudy thoroughfare of flashy clip joints and tourist traps” was indeed a sensation, at least among the magazine’s sedate audience. It was the first of many monthly stories, increasingly more important and readable, to follow in the next few years.

It was also the first time Fonzi became aware of an Inquirer reporter who was supposedly working on a similar story but whose work never appeared in the paper. Fonzi wondered why, and after several years of investigation, the answer came in 1967, when he and Greg Walter exposed Harry Karafin as a shakedown artist who was using his reputation as Inquirer publisher Walter Annenberg’s hatchet man to extort local businesses. That story still has shock effect almost 60 years later, and it gave the magazine a national reputation. It was also an exposé that required considerable courage to print, considering the possible legal implications of taking on a man as powerful and vindictive as Walter Annenberg. Herb Lipson not only showed that courage — he relished the role.

Not everything in our book was flattering to Herb — especially comments from those who worked for him in the 1970s, when he took over Boston magazine. But my guess is that Gaeton Fonzi’s tribute more than made up for any negatives. Fonzi died before the book appeared, so Herb never had the chance to thank him. But he did buy 500 copies. —Bernard McCormick

The Boss

Herb meeting Pope John Paul II in the early 2000s.

I first met Herb when I was 22, a journalism graduate fresh out of college, and I worked for him off and on, through eight editors, for more than 40 years. Technically, I was hired as a “gal Friday” by Alan Halpern, the beloved editor of Philadelphia magazine, who made me the writer I became. But there was never any question that Herb was The Boss. Back then, he hobnobbed with the movers and shakers of the city because he enjoyed the prestige of being part of the establishment elite, but more importantly because it gave him the opportunity to use the affable side of his personality to sell ads and build the reputation of his burgeoning magazine.

Herb had taste and class and was obsessive about presentation. He dressed impeccably in bespoke shirts and suits and expensive ties, and he had strong ideas about workplace attire. Woe to any writers who wore jeans to the office; they would be sent home to change.

Shortly after I was hired, Herb wanted me to arrange an office Christmas party. He sent me to the food court at John Wanamaker with a credit card and the admonition to buy an impressive spread of cheeses and pâtés but not to spend too much. Those Christmas parties grew into legendary affairs that were the choice holiday invitation all over the city. Yet no matter how lavish the food and drink, Herb always capped the evening by taking a few of the staff to Pat’s Steaks for a late-night snack.

Herb’s conflicts with his editors were legendary. Many a Friday, Alan Halpern would quit, only to be back behind his desk the following Monday or Tuesday after a series of cajoling phone calls from Herb. But where it really mattered, Herb had the savvy to bring on board superb editors and give them the license to do prize-winning journalism. In retrospect, we writers tended to give him much less respect than he deserved. He was a salesman, not a journalist, yet he had keen instincts for what made a good story. And he was a damn smart businessman, which none of us valued very highly even though it paid our salaries.

Over the years, Herb and I clashed ferociously about politics and our vastly different views of a just society, but we became colleagues and friends. I will remember him as the man who pioneered the new genre of city magazines and was a giant in that industry. —Carol Saline

The Dandy

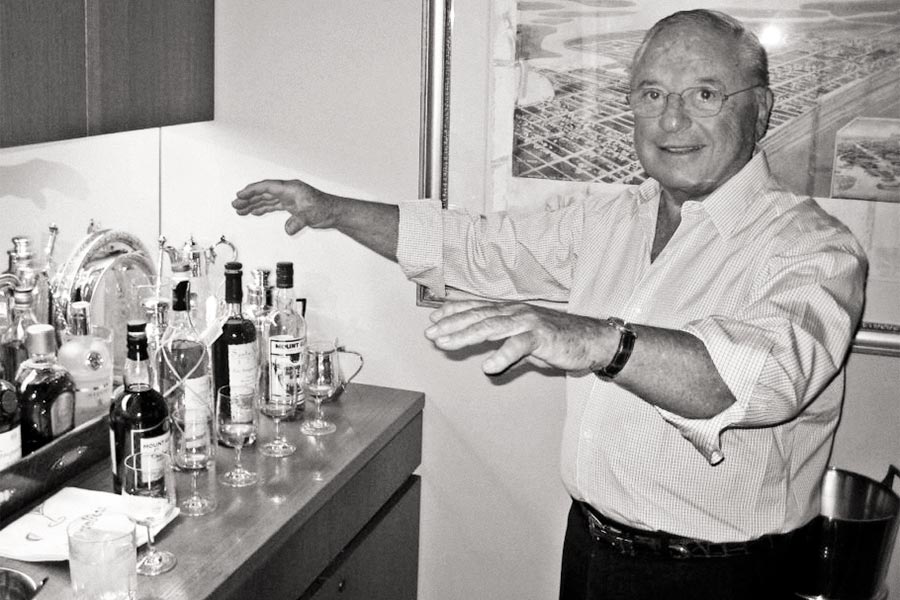

Herb preparing to pour a masterpiece in his Margate home.

He was a true bon vivant, the kind of foppish man-about-town you saw in old black-and-white movies. He crafted an excellent martini, always served on a silver tray. He obsessed over details: the cut of his crystal tumbler, the sourcing of his olive oil and mustard, the silhouette of his jacket. He believed in holding doors for women, in dining well and often, that you could tell a lot about a man by the way he danced. He was the only male I could ever picture wearing an ascot and not looking utterly ridiculous.

One could say much about Herb Lipson, and certainly, many have. I can add only this: He knew how to be a gentleman. You could have cut yourself on the creases in his pants. I never met another man who wore a plaid blazer with more aplomb, or who, despite a body short and stout, managed to carry himself so regally, sometimes to the border of pomposity. In demeanor, he could be both courtly and belligerent, sometimes at once. He was a man of strong and unwavering convictions, reflected not only in his scrappy columns, but equally in his belief in the rules of comportment and style. He constantly, wearily lamented the decline of Philadelphia’s code de la mode. He was known for wandering through interns’ cubicles, trolling for inappropriate office footwear. I once wore a pair of expensive French sandals to work in the summer, resulting in an apoplexy on Herb’s part so dramatic that he appeared to be in physical pain. Despite the theatrics, I think he was secretly appreciative I had dared to do it. Making a bold fashion statement was, after all, far superior to making no statement at all.

The seeds of his dandyism were sown early: As a boy growing up in the working-class Lehigh Valley, he favored tweeds and oxfords over t-shirts and jeans. (He told me his gruff father once asked him, with suitable exasperation, “Why do you always have to be fancy?”) By the time he was in his late 20s, he was waltzing with Gloria Swanson at Grace Kelly’s wedding in Monaco. He grew into a raconteur whose soapbox was a corner booth at the Palm — a shorter, Jewish Don Draper, without the stolen identity. Though that wouldn’t have particularly surprised me, either. He lived that kind of life. Thank God he knew how to live it well. —Michael Callahan

The Nose

One of Herb’s favorite words was nez. Nez is a French word. It means “nose.” Periodically, Herb would shuffle from his office to my desk and embark on a discourse about French vineyards. In these vineyards, he’d tell me, there was a person whose only job was to sniff the wine for suitability. By the time I got to know Herb, in 2013, he was starting to repeat his stories while also losing track of their details. When he forgot the title of the vintner he was describing for me, I could fill him in. He was called “Le Nez.”

I have no idea if such people really work at French vineyards. Herb may have been pulling my leg, or I may be bungling his depiction. (If so, I think he’d forgive me. Herb was more partial to the juniper berry than the grape anyway.) But he was obsessed with the nez for a reason. Great writers and editors — and publishers — had to have one. It wasn’t just a matter of being nosy, or sniffing out a story. There was subjectivity and romance behind good storytelling. You could smell it, or you couldn’t. And Herb always could.

There were aspects of Herb’s rakish humor and conservative politics that didn’t age well. It’s tempting to see his deep affection for print magazines in a similar vein, as a facet of his throwback persona. But his instinct for provocative long-form writing was timeless. One of his great parlor tricks was coming up with the titles of articles before the articles were written. His headlines were smarter and more amusing than anything the rest of us came up with later on. I came to Philly Mag as a 23-year-old, clinging to the notion that a career in narrative journalism was possible in the Internet era. One of my trusted sounding boards, and most persistent champions, ended up being 60 years older than me. Cheers to that. —Simon Van Zuylen-Wood

The Troublemaker

Herb and editor Alan Halpern with writers Greg Walter (left) and Gaeton Fonzi (right).

“You know what we need?”

You always knew when Herb was going to deliver something profound, because he would rock back and forth, like a penguin in wingtips.

“We need a story on Main Line wives who are also hookers.”

This is why I loved and will miss Herb Lipson.

Herb was a lot of things. He was a publisher who was unflinching in seeing that quality investigative journalism got its due — even if it meant fending off numerous lawsuits that almost buried his enterprise. He was a champion for his magazine’s reporters. He was fearless. He LOVED a great, juicy story, so, needless to say, we got along fine. He hated boring people and people who wore bad shoes. He was a Piece of Work.

Now, it’s true that Herb pissed a lot of people off. And not just the editors he fired. There was that time when he went after the Americans With Disabilities Act in his column, which I always called “Off the Cuff Link.” Suddenly there were dozens of people in wheelchairs rolling up to the offices to protest Herb. “Aren’t you mortified?” I asked him. And he did that penguin thing and said, “No! If they don’t love you or hate you, you’re doing something wrong.”

Herb never got the credit he deserved for creating the city magazine. It was a Philly thing. The media elite in NYC couldn’t possibly credit Herb Lipson (by the way, where is the NYT obit?) even though he also created Manhattan, Inc. But it was done by those two Philly guys — Herb and Alan Halpern. It’s impossible to talk about Herb without talking about Alan, who was like a fourth wife to Herb. They fought like Liz and Dick, breaking up, making up, divorcing, remarrying. But only Herb got the good jewelry. I came to know Alan first, soon after he was permanently banished from the Philly Mag kingdom after 29 years and had taken over a little rag called Atlantic City magazine, which was my first job out of Penn. (Who says an Ivy League degree won’t get you anywhere?) I learned very quickly not to bring up Herb’s name, because Alan might stroke out. Years later, at the pool at Society Hill Towers, I proudly presented my mentor with a cover story I’d written for Philly Mag. I thought by now he might have gotten over it. He stood up, walked over to the garbage can, and threw it out. When I told Herb this story, he got that twinkle in his eye: “That’s my Alan!”

In 1991, the editor in chief got fired over Best of Philly (!!) — long story — and I quit in protest. (P.S. Quitting in protest is very overrated.) Herb thought it was amusing that I quit (and knew I would eventually return — I did) but never stopped respecting me. Even years later, when I was working in NYC, he would call me when he and his wife, Carol, were coming to town, to take me out to dinner. We always laughed our asses off. And argued, too. That was the beauty of Herb. RIP, though I know you won’t. I’m sure you’re already making trouble. —Lisa DePaulo

The Malcontent

Herb, 1980s version.

Many things drove Herb crazy. When I was an editor at the magazine, we would have lunch occasionally. I have the habit of not wearing more than a sport coat at the height of winter, no matter how cold it is. Which meant that one cold day many years ago, when we were walking down Walnut Street headed to the Palm, Herb, whose head was adorned with a large Russian fur hat, insisted we make a left turn. Into Brooks Brothers.

“Herb,” I told him, “I don’t want a coat.”

“You need a coat.”

“Herb, no. Absolutely not. You’re not going to buy me — ”

He was already inside.

When we emerged from Brooks Brothers 20 minutes later, I was wearing a lined trench coat made of Bemberg cupro and wool and cashmere; it cost $500. Suddenly I could have passed for an investment banker instead of a journalist, and Herb, still wearing his large Russian fur hat, was quite pleased.

He had other issues with my comportment. Herb occasionally threatened to order a dumpster in to clean out the mess of papers in my office. He accused me of being a moron for my refusal to read the Wall Street Journal.

But you had to hold your ground with him. The day Herb bought me a coat was the only day I’ve ever worn it. I never cleaned up my office. The Wall Street Journal, though — that one he won, because the weekend edition is quite good.

You struck a stance with Herb because you felt vulnerable, as if you risked not just how you dressed or how neat your office was or what you read, but something more. Though Herb himself could not understand any path except striving to be sublime.

Which is why his city’s decline — as he saw it — drove him nuts, too. He could not understand why City Council was so incompetent and the shrinking business community so passive. He couldn’t get why no one fixed the sidewalks, or why cabs were so filthy, or why the inner city’s ship could not be righted. Herb would rant about these and other things, though the underlying feeling was more positive: He loved Philly, a beacon to him when he was a young man, where he made his success while the city was still more or less in its heyday and he became the Peck’s Bad Boy of local journalism. So what he saw as Philadelphia’s decline was personal, and he tried, through this magazine, to clean up the mess. To call miscreants to task, and to buff and shine his city. To instill a little class once again.

Today, I broke out the coat that Herb bought me 20 years ago and laid it out on my bed as if it was from another time, like a dress from Gone with the Wind. It’s a beautiful coat, and when I hung it back up, I did so very carefully. —Robert Huber

Mr. Brightside

Herb looking very Dick Cavett.

I worked at Philly Mag for quite a while without getting on Herb’s radar, which in some ways was a good thing. Once you were on Herb’s radar, he’d call you on the phone or come into your office and kvetch endlessly about how the writers and editors nowadays were all big chickens (though that wasn’t the term he used) and afraid to say what they really thought. Herb was never afraid to say what he really thought. He was like my father that way. My dad kept a big folder filled with clippings of news stories about TV ministers and “family values” politicians and similarly upstanding citizens who’d been caught molesting children or keeping mistresses or skimming off the till. For my dad, hypocrisy trumped all other sins. This was excellent preparation for working for Herb.

He and Philadelphia were a weird match, when you think about it. The “and most contented” part of Lincoln Steffens’s famous quote about our city made him crazy. Maybe if he’d gotten his start in, oh, say, Phoenix, or Seattle, or Omaha, he would have made a dent in the municipal corruption and been contented himself, instead of fighting with his staff up to the bitter end about the causes of poverty in West Philly, or the snowflakes on our college campuses, or the city’s chances of snagging that second Amazon HQ (which he pegged at nil). He had a way of poking at the holes in our lofty liberal theories with relentless relish, of forcing us to try to defend with words what we tended to believe ought to go without saying. Of course, it takes words to make a magazine.

We just wanted him to be careful. He never wanted us to be careful. He wanted us to be fearless and suspicious and cynical and in a constant state of outrage, even as we appreciated all the finer things in life. That’s a hell of a balance to maintain, which may be why Herb went through editors the way he did.

I never could decide if Herb and I got along so well because I was getting old or he was staying young. I always called him “Mr. Lipson” when we spoke on the phone, because I think he liked it. I think it made him remember his Mad Men days, when guys were guys and women were dames and people laughed when you told a good joke, even if it wasn’t PC. He was sure that people, just like Philadelphia, never really change — that in our hearts, we’re just as venal and selfish now as we were back in the Garden of Eden. Decade after decade after decade, this city proved him right. To have believed anything else would have made him, well, a hypocrite. —Sandy Hingston

The Life of the Party

Herb with his wife Carol in recent years.

I could tell you about my first weeks at the magazine in 1982, when Herb ordered me to get a haircut and then sent his assistant around every day to see if I had. (I hadn’t. Still haven’t.) I could tell you about the time he stormed into and out of my messy office, calling me an “unmade bed” — prompting one of my colleagues to actually buy a dollhouse bed he “unmade” for me. Or when he told the folks in the art department that I was “such a smacked ass” (and then we had to look up this antique insult).

I could tell you about my last day as his employee, in 2000, when he called me into his office to relieve me as editor. I pretty much talked him out of it — because one-on-one, once you calmed him down, he could be smart and reasonable — and then realized both he and I would be happier if I wasn’t editor anymore, ending my 18 years working for him.

And I could tell you how we finally made peace several years later and I returned as a freelancer — because I realized that all I had ever wanted to be was a writer at Philadelphia magazine, an experience made possible by Herb even as he hired and tortured and fired every editor and writer there I ever knew and loved.

Instead I’ll tell you about the single happiest moment I shared with Herb Lipson, which captures everything I’ll fondly remember about him — his love of good magazine writing, good food and grand gestures, and his love of family. In 1994, a story I did for the magazine won the National Magazine Award for public interest writing. The story had been really personal, but getting it into the magazine had been an extraordinary group effort, and the editorial staff partied to excess — first in New York, and later that evening in Philly, at the Palm.

Herb didn’t try to get involved with those parties (although we charged them to him). But after we were all home and sober, he told us that the editor in chief and I, and our spouses, should meet him on a certain day at a new restaurant people didn’t know much about, called Striped Bass. We were going to be the very first people to eat at a new foodie thing called the “chef’s table.”

We came in and sat down — the group included Herb, his kids David and Sherry and their spouses, the heads of finance and advertising and their spouses. And within minutes, we were being served an ocean of fresh seafood — piled up on tiers in the middle of the table — and bottle after bottle of good champagne.

Herb and I, and everyone else at the table, had the same lobster-eating grins on our faces. And that day, we just indulged together and celebrated the essential joy of magazines: that a bunch of people who sometimes don’t even get along very well decide to create, re-create and sustain a publication that matters to them, to their city, and to journalism. And every issue, you have to do it over again.

Herb has finally put his last issue to bed — he can’t make anyone tear up another cover at the last minute, or scare the shit out of another young writer. But I do wonder, now that he’s gone, who can replace what he did at his peak and even after — which was, consistently, put his money where his mouth was, trust the process of quality journalism (in words and in images), and create a high-functioning dysfunctional family who leave everything they have on the page. —Stephen Fried

Published as “A Man in Full” in the February 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.