Bring Back the Fairmount Park Guard

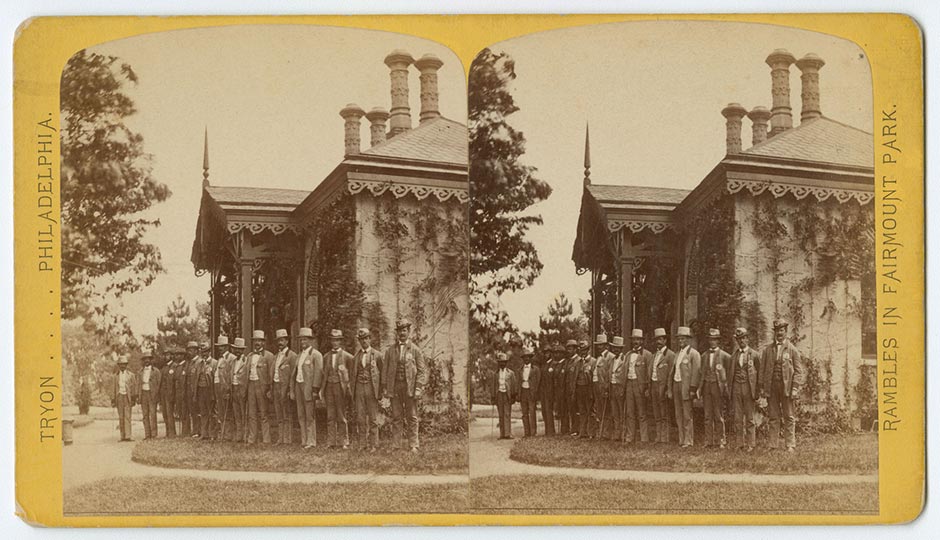

Stereoscopic image of Fairmount Park guards, circa 1880.

When the neighbors in expensive homes near Fairmount Park’s Devil’s Pool recently complained of trash, debris, and decadent behavior from the many visitors to Philadelphia’s rare geologic wonder, my first thought was, “Bring back the Fairmount Park Guard.”

The Park Guard, an elite troupe of policemen whose job it was to patrol the park on horseback, was subsumed into the Philadelphia Police Department in 1972 by then-Mayor Frank Rizzo. Since then the park has never been the same.

I first visited Devil’s Pool as a boy when an aunt orchestrated a field trip with walking sticks. Our mission was to find the Massey Rhind-designed wooden sculpture of Chief Tedyuscung, the last Lenni Lenape chief to leave the Delaware Valley. We never did find Tedyuscung, who with other members of his tribe was burned to death in their house after a drunken frolic, but we did stumble into the area known as Devil’s Pool.

At Devil’s Pool we spotted a group of boys jumping off cliffs into the deep water below and then climbing back up the cliffs in order to jump again. These jumpers did not come with campout accruements like Styrofoam coolers, beer or unused needles. They were jumping on the sly and had to be ready to vacate the premises in a second. The rustic scene was straight out of Thomas Eakins’s painting The Swimming Hole.

The Devil’s Pool jumpers in 1960 were mainly white. Many jumped in their underwear and some were nude. Nobody jumped from the towering aqueduct above the cliffs. In 1960 I think this would have been considered suicide. The scene was probably pretty much as it was during the Centennial Expo in 1876. The old wooden bridge, albeit reinforced, and gazebo that overlooked the pool was no doubt the same one that tourists saw in the 19th century.

Ten years ago I returned to Devil’s Pool with a friend and was shocked to see graffiti scrawled on tree trunks and boulders. There was also litter, which you never saw when the park guards patrolled the area on their horses.

Devil’s Pool is now a kind of pop-up Shangri la, a private retreat. Rich or poor, most people relish the idea of getting away from crowded city streets, especially when the modus operandi for pedestrians these days seems to be to keep pace with traffic patterns: keep walking, keep moving, and never sit anywhere outside the strict parameters of a city park or “authorized” areas because this will around suspicion. This is why a spot like Devil’s Pool is considered gold.

In 1960 Valley Green was mostly the “hiking” province of people from Chestnut Hill, or “people with breeding,” as my great aunt used to say. People from Chestnut Hill even had their own entrance to the park, while “commoners” had to approach it by traveling to Henry Avenue in Roxborough and then take Forbidden Drive to the horse stables. Devil’s Pool was a relatively hidden spot before the age of social media.

Valley Green did not have a litter problem then, thanks mainly to the impressive horsep-trotting guards in their thigh-phigh black boots and Smokey the Bear hats. While the guards may have played cat and mouse with the Devil’s Pool jumpers, my guess is that the kids felt sufficiently intimated that littering just wasn’t an option.

The concern of Devil’s Pool neighbors on Mt. Airy Avenue reminds me of the confluence of trash, litter, and assorted property damage that affected Historic Strawberry Mansion a couple of years ago when nearby Dell concertgoers would leave behind cooking grills, garbage, and even tampons on the Strawberry Mansion property site after piggybacking outside the official concert area. Had there been Fairmount Park guards on patrol during Dell concerts, I’m convinced that the problem at the Mansion wouldn’t have gone on as long as it did.

Resurrecting the Fairmount Park Guard would not only add color and flair to Fairmount Park it would also be a boon to tourism. More important, those old park guards really cared about litter, which is not something that you find high on the priority list of the average Philly cop.

Thom Nickels is a journalist and author of 11 books, including Philadelphia Architecture, Spore, and Literary Philadelphia. He was awarded the Philadelphia AIA 2005 Lewis Mumford Award for Architectural Journalism. He’s written for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Daily News, New Oxford Review, and many other publications.