When Children Force Us to Remember What We’d Rather Forget

Photo Credit: Peter Morgan | AP Photo

If you’re a newcomer to Philadelphia, chances are you’ve walked by the Municipal Services Center and paid very little attention to the statue that stands in front of it.

The statue is one of Frank Rizzo, the city’s former mayor and police commissioner. Because incidents like the death of David Jones at the hands of Officer Ryan Pownall during a traffic stop were pretty commonplace during Rizzo’s watch, there have been more than a few calls for his statue to go the way of many Confederate monuments.

In the Rizzo era, police brutality was more commonplace than it should be. The best-known account of this was the time Rizzo’s officers strip-searched members of the Black Panther Party in front of a Philadelphia Daily News photographer. It wound up on the front page.

It’s Philadelphia’s history of police abuse that has led to the creation of a historical marker commemorating the May 13th, 1985 confrontation between Philadelphia police and the Black nationalist group MOVE. Unfortunately, it’s a marker without a home at the moment.

That’s because, while there are more than a few monuments here in Philly that might memorialize things we’d rather forget, like, say, where the father of our country kept his slaves, this will be the first one commemorating an act of police brutality.

And let’s be honest with ourselves. No matter how badly Philadelphia might want to run away from this part of its history, there’s no other way to describe any incident that ends with police dropping a bomb, killing 11 people, and destroying a city block.

While studying police brutality in history class, a group of students from the Jubilee School, a private academy in West Philadelphia that has such neat things as an anti-violence club, learned about the MOVE bombing and decided to visit the spot where it happened, according to Karen Falcon, the school’s founder and principal.

They felt it deserved a historical marker, so they went to the block’s remaining residents, got petitions signed, and sent them to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission to make it happen. (How the residents of the 6200 block of Osage Avenue have been screwed time and time again by the city of Philadelphia since 1985 is another column for another day.)

In addition to the $500 they raised for the marker through a GoFundMe page, the students also received $500 from state Senator Anthony H. Williams toward the $1,000 needed to create it.

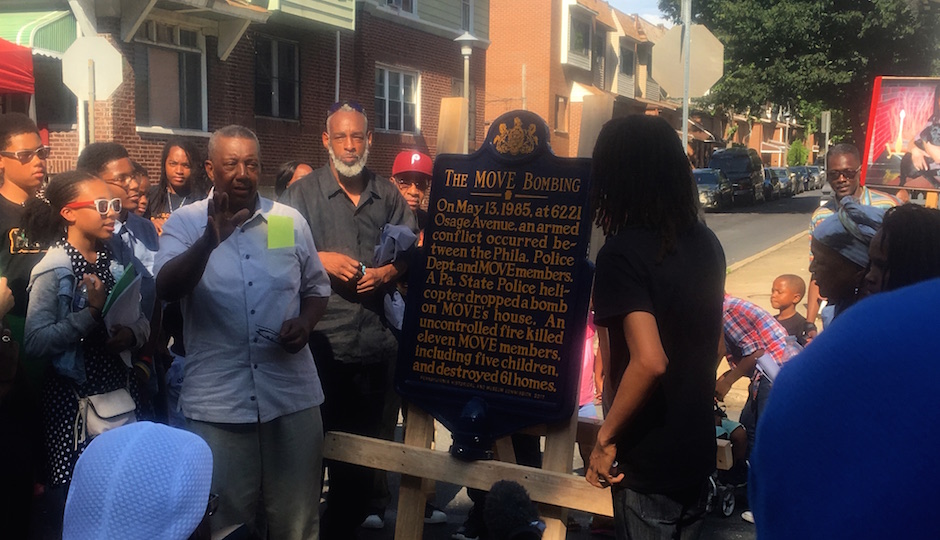

The marker was recently unveiled at a ceremony at the intersection of Cobbs Creek Parkway and the 6200 Block of Osage Avenue. But whether or not it eventually gets placed there or in front of the house at 6221 Osage Avenue is up in the air right now. The streets department is waiting for instructions from city officials on what to do next.

Gerald Renfro, one of the few remaining homeowners on the 6200 Block of Osage Avenue, and Arnett Woodall, the owner of West Phillie Produce, unveiled the MOVE bombing marker. Woodall helped students get the petitions for the monument signed. | Photo by Christopher S. Murray

Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell has pledged to use her political might toward finding a place for it.

Considering what the marker symbolizes, she may have to.

To say that we as a city have never completely dealt with MOVE and its aftermath is possibly the understatement of the millennium. I still remember seeing the beginnings of the confrontation on NBC 10 when I left for my classes at Temple that morning, then coming home that evening and seeing the buildings not only in flames, but being allowed to burn. It’s not the sort of thing you forget.

When your city, a city that had already been synonymous with police brutality, makes national and international headlines because police were allowed to drop a bomb on a city block without anyone going to jail, that might be something you want kept off the tourism guides.

Even if that might be exactly where it belongs.

Denise Clay has been a journalist for more than 25 years, covering politics, education, and everything in between. Her work regularly appears in the Philadelphia Sunday Sun and the Philadelphia Public Record, and has also appeared on the BBC, XO Jane, and Time.com.