11 Things You Might Not Know About Thaddeus Kosciuszko

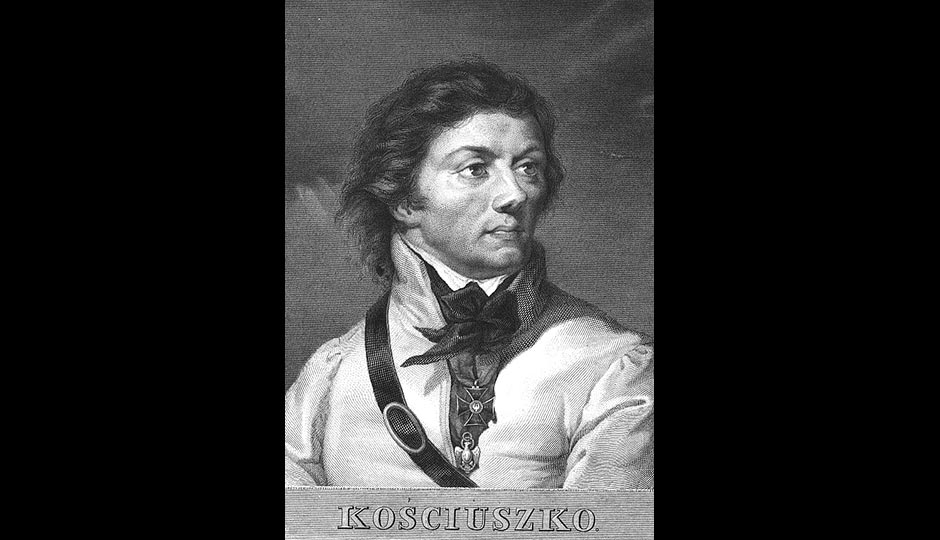

Image: Public domain/Wikimedia Commons

Tomorrow, February 4th, is the 271st birthday of the most famous Polish figure in American history, Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (a.k.a. Thaddeus Kosciuszko), the dashing, handsome Revolutionary war hero whose national memorial stands at the corner of 3rd and Pine. Here are 11 things you might not know about him.

1. Kosciuszko (say “Ko-SHUS-ko”) was born in the village of Mereczowszczyzna (say — oh, the hell with it) in what is now Belarus but was then part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He was the youngest son of an officer in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Army; his family held a modest amount of land that was worked by 31 families of serfs. Sent to France at age 20 to study, Kosciuszko returned to Poland a few years later, found his brother had squandered the family’s (small) fortune, and nonetheless tried to elope with his nobleman landlord’s daughter. The landlord’s men beat him bloody, so he headed for the USA, having heard there was a revolution in progress and being pro-revolution generally.

2. In August of 1776, Kosciuszko applied to the Continental Congress and was assigned to the Continental Army. He had studied artillery and fortifications in Paris, and his first job, at the request of George Washington, was to fortify Fort Billingsport in Paulsboro, New Jersey, to prevent the British from sailing up the Delaware to Philly. The land for the fort was the first land purchase ever made by the United States (in the form of the Continental Congress). Kosciuszko’s first boss was Ben Franklin, but by October he’d been commissioned a colonel of engineers in the Continental Army.

3. He was then sent to Fort Ticonderoga, on the border between the U.S. and Canada, to review its defenses. He recommended construction of a battery on a high bluff above the fort, but its commander rejected the idea. When British General John Burgoyne attacked Ticonderoga in July 1777, he did so from the high point, and the fort fell. In the subsequent retreat by Continental soldiers, Kosciuszko was called on to come up with some way of delaying the pursuing British army. He and his men built dams and destroyed bridges, creating a marsh that bogged down the enemy, and the American forces safely escaped across the Hudson River.

4. The defenses Kosciuszko planned and constructed at Saratoga withstood British attacks, and Burgoyne surrendered there in October 1777. The defeat is considered a turning point in the Revolutionary War, since it spurred the French and Spanish to join the American fight against the British. Kosciuszko found time that year to compose a polonaise for the harpsichord; the tune became a popular anthem during Poland’s November Uprising in 1830-’31.

5. It was the maps and plans for the fortifications Kosciuszko built at West Point that Benedict Arnold stole and attempted to convey to the British. Arnold’s go-between, Joseph Stansbury, was introduced to the Loyalist poet Jonathan Odell by William Franklin, Ben’s Loyalist (and illegitimate) son, who was governor of New Jersey at the time. Franklin then introduced Stansbury to British Major John André, who was courting beautiful, lively Philly socialite Peggy Shippen. After André was captured and hanged as a spy, Peggy married Benedict Arnold.

6. After his work at West Point, Kosciuszko headed to South Carolina, where he built boats and fortifications, enlisted informers, scouted territory, and generally did pretty much everything that would enable the Continental Army to outrun the British during the “Race to the Dan” retreat across North Carolina. The thus-preserved Continental forces then regrouped, recrossed the river, and confronted the troops of British General Charles Cornwallis, effectively routing them and taking the South. In fighting at Ninety Six, South Carolina (sorry; no one knows where the name came from), Kosciuszko suffered his only Revolutionary War battle wound when he was bayonetted in the buttocks.

7. Kosciuszko was in Charleston, South Carolina, when the Treaty of Paris ended the war in April 1783. After taking time out to plan the fireworks for Princeton, New Jersey’s Fourth of July celebration that year, he set about trying to collect the back pay for his seven years of military service. He didn’t even have enough money to return to his homeland; plenty of other officers were in the same boat. Like many of his peers, Kosciuszko lived on money he borrowed from Philadelphia financial broker Haym Salomon. Legend says George Washington arranged the 13 stars on the first American flag in the shape of a Star of David in honor of Salomon’s monetary contributions to the war effort; Salomon died, penniless and in prison, in 1785 at age 44, and is buried in Mikveh Israel Cemetery at Spruce and South Darien Street. Kosciuszko was eventually given a certificate for $12,000 and 500 acres of land, but only if he stayed in the United States. With the war over, he moved on.

8. Back in Poland, he reclaimed some lost family land and took up farming. But after he limited the service his male serfs owed the lord of the manor to two days per week and exempted female serfs completely, production dropped off, and Kosciuszko accumulated debts. After the adoption of reforms at the Grand Sejm, he lobbied for creation of a Polish army based on the American model and eventually was commissioned as an officer, with a salary that alleviated his debts. He was disappointed when the nation’s new constitution of 1791 retained the monarchy and did little to better the peasants’ lot. Reactionaries trying to overthrow the constitution enlisted help from Russia, which was happy to invade the new Commonwealth with a force three times the size of Poland’s, beginning the Polish-Russian War of 1792.

9. Though Kosciuszko never lost a single battle, the Polish king, Stanislaw August Poniatowski, capitulated to the Russians. Horrified, Kosciuszko traveled through Poland and Ukraine, attracting adoring crowds, before settling in Leipzig, where, with like-minded patriots, he began to plot a revolt against the victors. After the Sejm was forced to rescind the constitution, Kosciuszko mounted the Kosciuszko Uprising in March 1794, marching on Warsaw with an army of 6,000 men and calling for civil rights and reduced workloads for the nation’s serfs. Alas, the Prussians, under Frederick the Great (the guy that King of Prussia’s named for), threw in with the Russians, under Catherine the Great (King Stanislaw’s ex-lover), and in October, Kosciuszko was captured and imprisoned. At the subsequent Battle of Praga, the Russians killed 20,000 Warsaw residents.

10. After the death of Catherine the Great in 1796, her son, Paul I, granted amnesty to Kosciuszko on the condition that he never return to Poland. He sailed for America, installed himself at 3rd and Pine streets, befriended Thomas Jefferson (who called him “as pure a son of liberty, as I have ever known”), flirted with and sketched the local ladies, then left America for France and later Switzerland, where he died in 1817 after falling from a horse. He was 71. His body was first buried in a Swiss church, then removed to Krakow and interred in a crypt with Polish saints and kings; the local populace raised a monument to him built of dirt from all the battlegrounds on which he’d fought. His internal organs, removed at his embalming, were buried separately in Switzerland, except for his heart, which was kept in an urn at the Polish Museum in the Swiss town of Rapperswil until it was sent in 1927 to Warsaw, where it’s now in the Royal Castle.

11. On his last trip to Philadelphia, Kosciuszko enlisted Thomas Jefferson as executor of a will directing that his military pay from the Revolution be used to buy the freedom of American slaves and pay for their education.