Civil Rights Lion Julian Bond Was a Bucks County Cub

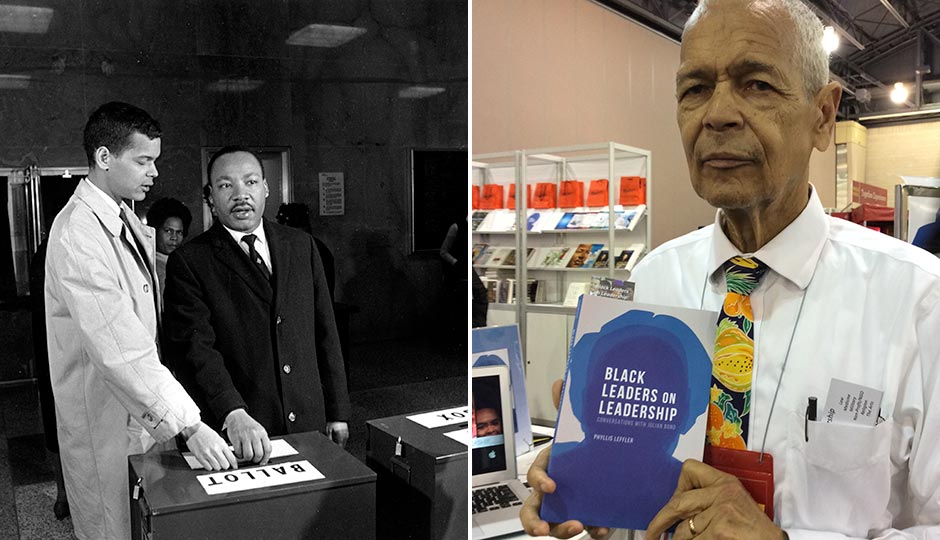

Julian Bond, left, with Dr. Martin Luther King in 1966 (AP), and right, with the last book he authored in Philadelphia for his last major public appearance at the 2015 NAACP conference (Bobbi I. Booker).

A couple years ago, I was strolling through Philadelphia International Airport when I came across the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University Libraries photo exhibit of the late John Mosley, a society photographer of Philadelphia’s Black elite.

I eventually came to a full stop as I took in the images, pondering the lives of those who existed before me. Many of the people portrayed where long deceased, but there was one picture of a little boy that I instantly recognized. Standing next to entertainer and social activist Paul Robeson was an 8- or 9-year-old Julian Bond, fully possessed of himself and the moment. When the longtime civil rights activist died last weekend at age 75, I couldn’t help but to reflect on that long-ago picture that showed a slave’s grandchild and a college president’s son at the beginning of a life of activism.

Bond, who died last weekend, was born in Tennessee, and was raised in the Philadelphia area after his father, Dr. Horace Mann Bond, returned in 1945 to serve as the first African American president of Lincoln University, the nation’s first Black college. While Lincoln’s president, the elder Bond became friends with art collector Albert C. Barnes, the founder of the Barnes Foundation in Merion. Eventually Barnes restructured the foundation to enable the historically Black college to control the foundation board of trustees and oversee the art collection.

Bond resigned from Lincoln, his alma mater, in 1957 — the same year Julian Bond graduated from George School, a private Quaker high school near Newtown, Bucks County (where he was one of the few African American students in attendance). Years later, Bond would tell how his first date with a white student rankled his classmates. However, according to the school’s website, during a 2011 visit Bond credited George School with introducing him to non-violent social change and individual community service.

The lessons Bond learned while living in the Delaware Valley were further enhanced when he joined a select group of eight Morehouse College students to study with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the civil rights movement gained momentum in the mid-1960s. At age 20, Bond left college to co-found the legendary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC (pronounced “snick”) was the #BlackLivesMatter movement before social media existed.

Bond served as communications director of SNCC, traversing the Jim Crown South, bringing the world’s attention to disenfranchised Blacks struggling to survive within a white power structure. He organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. He courageously participated in Freedom Rides to register Black voters in the South. Bond was the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center in 1971, and marched into the new millennium as chairman of the embattled National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He was an emeritus of both organizations for the rest of his life, with the Library of Congress naming him “A Living Legend” in 2008.

A charismatic speaker, Bond was never out of the public eye and actively campaigned for social justice throughout all of his life. He was a tireless fighter in the climate change movement – opposing the Keystone pipeline long before others did. Bond also was a passionate ally in the fight for LGBT rights, and boycotted the funeral services of Coretta Scott King because they were held in an anti-gay church which was in direct opposition to Mrs. King’s strong support for LGBT rights.

Bond even returned to his Philly-region roots when he spoke out as an opponent of the relocation of the Barnes collection from Merion to Center City. In the 2009 documentary The Art of the Steal, the activist recalled Barnes’ specific provisions for the collection after his death, giving Lincoln University the power to nominate most of the trustees to run the foundation. “It is a crime,” said Bond. “And after all, it was Albert Barnes’ art. He owned it, he could decide what to do with it.”

Ultimately, long before Julian Bond grew to become a lion in the civil rights movement, he was a Bucks County cub, learning at a Quaker school how to be a thinker while negotiating for the rights of all people, regardless of race or sexual origin. The lessons Bond gleaned while living in the Delaware Valley helped steer this nation through a decades-long arc of social changes. William Penn, the Quaker leader and state of Pennsylvania founder, once wrote: “A good end cannot sanctify evil means; nor must we ever do evil that good may come of it.”

Thank you, Julian Bond, for your embracement — and diligent lifelong practice — of non-violent activism that touched on a form of sacred community that helps hold the world together.

GodSpeed …

Follow @BobbiBooker on Twitter.