50 Years After Bloody Sunday, a Push for Racial Fairness in Sentencing

I caught up with State Sen. Vincent Hughes on Sunday afternoon by phone — he had spent the weekend in Selma, Alabama, joining the 50th anniversary celebration of the “Bloody Sunday” march that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act, and was driving with former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick to the airport to return home.

“Pretty powerful,” Hughes, the Philadelphia Democrat, told me. “Pretty powerful to stand on the same ground where, 50 years ago, people were beat in the head … just to secure the right thing, was just a powerful thing.”

“People took charge of their own destiny, and they changed the country in a meaningful way,” Patrick added. “That’s an important lesson about the power we have when we look up instead of looking down.”

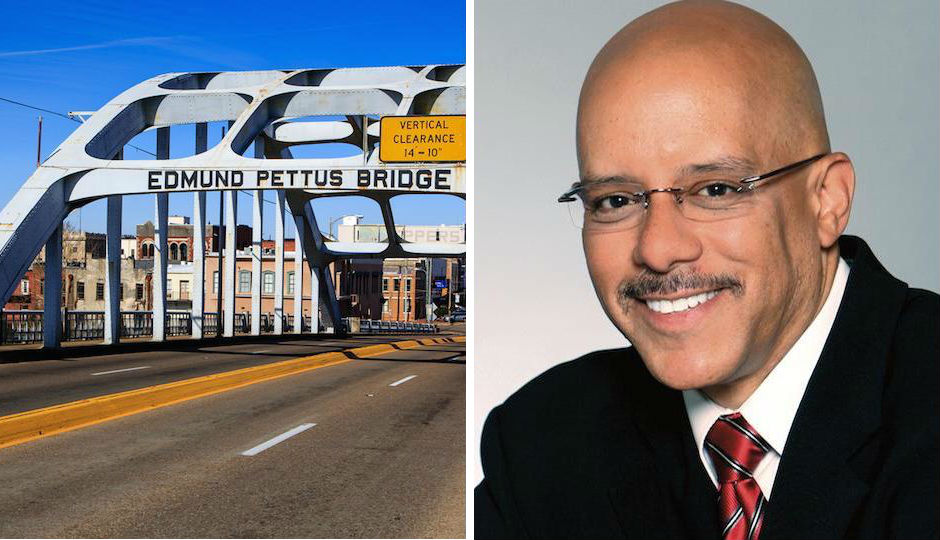

President Obama’s Saturday speech at the Edmund Pettus bridge, honoring the marchers and placing them in the context of generations of Americans who have strived to help the country live up to its ideals, had been singled out for particular praise in a weekend full of thoughtful oratory.

“It was a very powerful image, to see him in front of the Edmund Pettus bridge,” Hughes said of the president. “It recognized the work that has been done, and it recognized the work that needs to be done.”

Actually it was the “work that needs to be done” category of things that led me to speak to Hughes in the first place. Before he left for Selma, Hughes on Friday had introduced Senate Bill 424, which would let Pennsylvania legislators ask the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing to report on the disparate racial impact that might be the result of any new bill or amendment that would change the state’s criminal and sentencing laws.

Long story short: Hughes wants to be able to know if changes to state law will end up putting more black men behind bars.

“The penalties we have — that white community gets punished at one level and the black community gets punished at a higher level — that has to be researched, analyzed, and worked against,” Hughes told me.

Unfinished business

There’s good reason to believe that even now, 50 years after African Americans at Selma helped assure themselves a hand in writing the nation’s laws, those same laws — sometimes intentionally, sometimes not — can still be used oppressively against minorities. Last week’s Justice Department report on Ferguson offers proof of that.

And locally, one reason that marijuana decriminalization passed in Philly was because there was strong evidence that whites and blacks use the drug at about the same rate — yet African Americans were many times more likely to be arrested, go to jail, and end up with a permanent criminal record as the result of that use. Overall in Pennsylvania, Hughes said in a sponsorship memo, “the rate of incarceration for Latino individuals is roughly four times greater than white individuals, and the rate of incarceration for African-Americans is nine times greater than that of white individuals.”

Hughes wants to get in front of such trends, which can have devastating effects on individuals and the communities they leave behind when they go to prison.

“We need to do a better job of achieving justice, true justice, in Pennsylvania,” Hughes said.

On Sunday, at least, Hughes was able to draw a straight line between the events of Selma in 1965 and his ability to fight for such legislation.

“I’m not a state senator if not for those individuals who tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge,” Hughes said. “If they didn’t do that work, I’m not in elected office right now. We stand on their shoulders to do our work.”

Follow @JoelMMathis on Twitter.