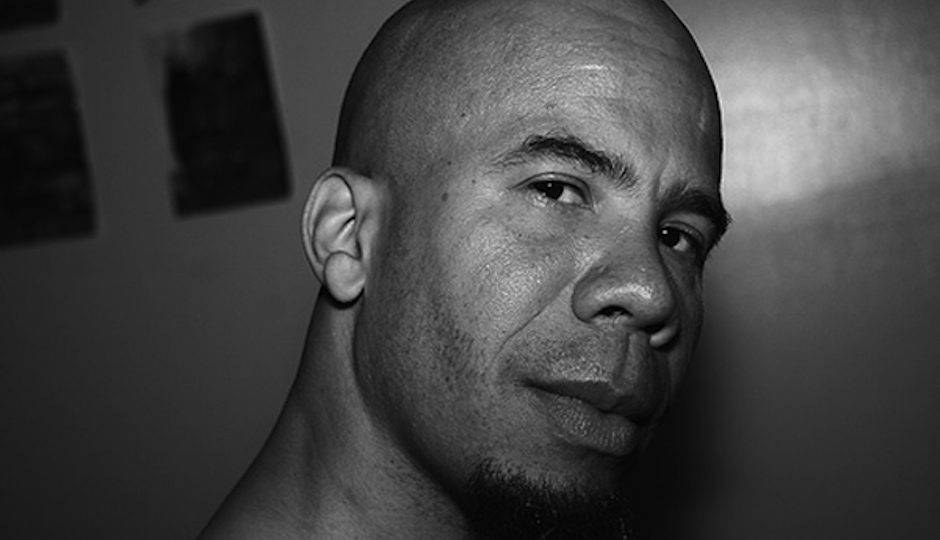

Steven G. Fullwood: Cultural Producer, Keeper and Animator Archival

Steven G. Fullwood

Few Philadelphians are aware that they live just a couple of hours away from the country’s most robust archival resource for Black queer materials: the IN THE LIFE ARCHIVE (ITLA). Steven G. Fullwood founded the Black Gay & Lesbian Archive in 1999, and in 2013 renamed the archive the IN THE LIFE ARCHIVE in honor of Joe Beam, editor of In The Life: A Black Anthology. The archive is housed at the Schomburg Center, a research branch of the New York Public Library.

Fullwood created the ITLA to aid in the documentation and preservation of cultural materials produced by and about LGBT people, Same Gender Loving, queer, questioning, and “in the life” people of African descent. Currently, Fullwood is the head of the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.

Steven Fullwood took some time out of his busy schedule to speak with me about archival evidence of Black queer participation in the Stonewall Riots, Black queer life during the mid-20th century and his work as a cultural animator, keeper and producer.

The movie Stonewall was under fire before its premiere for its lack of inclusion of people of color. Based on your archival work, experience and research, can you give me a sense of the role of Black LGBT people and activism during the Stonewall Riots? Can you recommend any sources for people who are interested in learning about the role of Black people as it relates to the Stonewall Riots? We recently acquired the papers of Storme DeLarverie, Stonewall veteran and civil rights activist, who died in 2014. She is credited with throwing the first punch at the Stonewall Uprising in 1969. The bulk of the her papers are photographs that document her work as a male impersonator and her MC work with the Jewel Box Revue who’s motto was “25 Men and 1 Woman,” and she, of course, was the one biological “woman.” Sadly, outside of the small material for Storme DeLarverie, there’s not a lot of archival evidence in the stacks at the Schomburg about the Stonewall riots. In the “In the Life Archive,” there is a small file for Marsha “Pay it no mind” Johnson, a trans woman credited with “really getting [the rebellion] started.” Thank goodness for the documentary on Johnson, Pay It No Mind: The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson, or we might not know anything about this pioneer. The library does not hold any primary resources for Sylvia Rivera, a Puerto Rican trans activist. Can you imagine what it was like for these two young activists who a year later after Stonewall co-founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) to work with homeless youth in the climate of hatred and violence towards transpeople? Remarkable and inspiring. Founded in 2002, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP), an organization dedicated to ending gender identity discrimination and poverty, seeks to carry on Rivera’s work on behalf of marginalized persons. And in 2005, a street in Greenwich Village near the Stonewall Inn was renamed in Sylvia Rivera’s honor.

Outside of the life and writings of mainstream names such as Bayard Rustin, Audre Lorde and James Baldwin, I feel as though we know very little about Black gay and lesbian life during the time period of the 1950’s and 1960’s. From your archivist work at the Schomburg Center, have you found enough historical material to speak to the cultural climate and landscape of Black lesbian and gay life during this time period? No, not at all. There are hints here and there about what Black LGBTQ/SGL (which was not widely used nomenclature at the time) life and culture was like at that time, but nothing comprehensive, and there are simple reasons for this. This absence of presence speaks to the times. There were no organizations producing culture, few books, no films, virtually no record of this time via that kind of documentation. The lack of cultural production during the first half or so of the 20th Century speaks largely to an invisible public presence. But, of course, there were people “in the life,” a term to describe black people involved in queer life, and sometimes criminal activity (e.g., number runners). Meeting spaces such as bars, parties and get-togethers in people’s home didn’t advertise, that is, create and distribute flyers about their “illegal” activities.

Probably the best well-known representation of gay life was the drag balls (also known as “Faggots’ Balls), held in Harlem at the Hamilton Lodge. These spectacles were written about in the Amsterdam News, Jet, and other papers in the 1930s and 1940s, but from a sensational point of view, not from the viewpoint of black queer people.

The Schomburg doesn’t hold a significant amount of letters and diaries where people describe their sexual lives. One unique example comes to mind: African-American dance critic, dancer, and researcher William Moore. In one of his diaries, Moore’s in France and laments the fact he is scheduled to leave the day that “fleet is coming in,” that is, a bunch of sailors. He also talks about a lover, virtually unheard of in black queer cultural archival history. This is the late 1960s.

By the 1970s, black queer social groups and political organizations began to surface including the Salsa Soul Sisters (now the African Ancestral Lesbians United for Societal Change) in 1974, and the National Association of Black Gays and Lesbians in Washington, DC in 1979. But to return to your original question, scholars and researchers will likely continue to unearth the presence of Black queer life through primary resources such as diaries and letters. Archives hopefully will work to acquire this material. And of course, there are people who lived through that time still alive and should have their oral histories recorded and transcribed to help fill in those mid-20th Century gaps and silences in Black queer history.

I have always been curious about Black LGBT life during the 1930’s, for someone coming of age during The Harlem Renaissance. The 1920s and 1930s shaped Black culture for generations and influenced American society. Has the center been able to collect materials that would shed light on the influences of sexuality, and perhaps the intersection of Black culture, art and sexuality during this time period? Absolutely, but primarily through the acquisition of books and secondary resources produced by and about Harlem Renaissance writers, thinkers, and artists such as Alain Locke, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Wallace Thurman, and Richard Bruce Nugent, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, “Moms” Mabley, Mabel Hampton, Alberta Hunter, and Gladys Bentley, to name a few. Zora Neale Hurston did not identify as lesbian but helped to lay a foundation for black lesbian and bisexual writers of the late 20th century to include sexuality as central to their creative and critical work including, but not limited to Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Cheryl Clarke, and Barbara Smith. Similarly, Joseph Beam’s seminal text, In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology, served in part as coming out party for new Black gay writers, and a reclamation of Black gay writers such as Richard Bruce Nugent and Samuel R. Delany. A few books to consider include: Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance: Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent, by Richard Bruce Nugent; Women of the Harlem Renaissance, by Cheryl A. Wall; Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, by A. B. Christa Schwarz; and Claude McKay, Code Name Sasha: Queer Black Marxism and the Harlem Renaissance, by Gary Edward Holcomb, among other books, as well as critical articles such a Mason Stokes’s “Strange Fruits: Rethinking the Gay Twenties,” published in Transition journal in 2002.

I read this statement by you in a previous interview: “My personal and professional work centers around three areas: cultural producer, and culture keeper and a cultural animator”. Can you elaborate on what this means and how your life and work speak to each of these three areas? Sure. The problem is that I think I can do anything (laughs.) Which means, of course, I can’t, but I don’t let it stop me. When I want to do something, I do it. Whether I succeed or fail is hardly the point. In 2004 I founded Vintage Entity Press and in 11 years we have published seven amazing books, including poetry collections by Cheryl Boyce Taylor, G. Winston James, and Pamela Sneed, a book nonfiction by Herukhuti, an anthology dedicated to the work of Joseph Beam (with Charles Stephens), a book of humor by yours truly, and a bibliography of black LGBTQ/SGL books co-edited by Lisa C. Moore and co-published by RedBone Press.

Additionally, I have had the privilege and opportunity to co-create exhibitions such as “Donald Andrew Agarrat: Harlem Photographer” and most recently “Epistolary Lives, Letters by Black Gays and Lesbians,” which was a part of the Schomburg’s “Curators’ Choice: Black Lives Matter” exhibition earlier this year.

When I refer to myself as a cultural keeper, I’m specifically referring to my work at the Schomburg first as an archivist, and then as a curator. Archiving black culture is an act of resistance, a necessary endeavor when countering the narrative of black pathology so prevalent and insistent in the media and American imagination.

A friend of mine once called me a cultural animator, and after I looked it up the meaning of the phrase, I agreed. Cultural animation, from the French animation socio- culturel, describes community arts work which literally animates, or “gives life to,” the underlying dynamic of a community. As in the creation of the In the Life Archive, or through my independent press, Vintage Entity, both of which focus on black LGBTQ/SGL life and culture. My community named me, and that feels good. Useful.