Is Philly Doing Enough to Save Cardiac Arrest Victims?

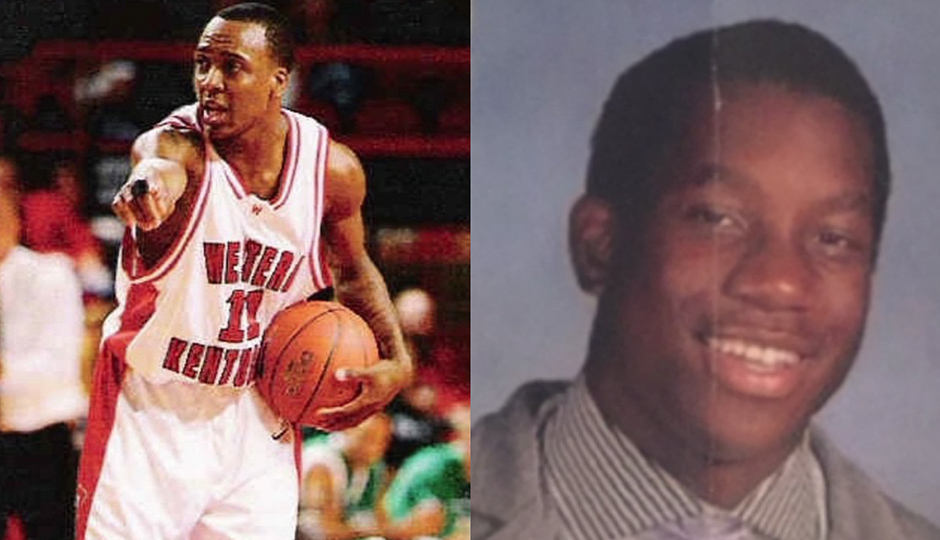

L to R: Philadelphia student athletes Danny Rumph and Ryan Gillyard died 10 years apart of the same heart condition. | Photos courtesy of Marcus Owens and Twitter

Last April, 15-year-old St. Joe’s Prep student Ryan Gillyard collapsed while jumping rope at his football team’s conditioning workout. Gillyard had undetected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a genetic disease that made his heart muscles abnormally thick, interfering with that organ’s ability to pump blood.

When the Inquirer covered the teenager’s death four months later, it became clear that an automated external defibrillator — the portable medical device that could have delivered a lifesaving shock to Gillyard’s body — was available at the practice field where he fell, but wasn’t used during the emergency. “The reason,” the newspaper said, “was unclear.”

Ten years before Gillyard died, another star athlete with the same condition collapsed during a pick-up basketball game at a Mt. Airy recreation center. The building where 21-year-old Danny Rumph was shooting hoops didn’t have a defibrillator. On Mother’s Day 2005, Viola Owens watched helplessly as her only son passed away. It took 31 minutes for an ambulance to arrive on the scene. By that time, it was too late.

In 2013, with some help from the fire department, Owens installed defibrillators in all 150 of the city’s recreation centers. But many Philadelphians still don’t know how to use those devices, or how to administer CPR. More often than not, studies show, bystanders like Owens are powerless when the unthinkable happens. And what good are emergency response tools if few people know how to use them?

•

Cardiac arrest is relatively common. It affects 400,000 people across the country annually and kills about 350,000 — more than lung cancer, breast cancer and AIDS combined. In Philadelphia alone, 1,500 people suffer from cardiac arrest every year. Often mistaken for a heart attack, cardiac arrest occurs when the heart stops beating entirely. (During a heart attack, blood flow to part of the heart is blocked.)

Gillyard and Rumph experienced their attacks outside of a hospital. The chance of surviving incidents of that kind in Philly is relatively low: 6.1 percent in 2015. Comparatively, about 10.2 percent of people nationwide survive after suffering cardiac arrest. Experts attribute this disparity to inadequate reactions by bystanders and substandard response times by the city’s Emergency Medical Services.

These numbers come from the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), a database that allows communities around the country to log their own cardiac arrest rates and compare them to statistics at a local, state and federal level. Philly began using CARES in 2012, and since then, the city’s overall survival rate has remained about the same. In 2012, it was 6.2 percent; in 2014, it was 6.7 percent.

In contrast, Montgomery County’s out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival rate in 2015 was 8.3 percent.

In other words, if your heart fails in Philly, the odds that you’ll survive are notably less than if you collapse in the county next door. To make matters worse, Philadelphians are actually more likely to suffer from cardiac arrest than their suburban neighbors: There are 7.6 cardiac arrests per 10,000 people each year in the city, compared to 5.4 in Montgomery County.

Another major difference: Montco has publicized its CARES data — something that the Philadelphia Fire Department flatly refuses to do. Philadelphia magazine obtained the city’s figures from sources within the fire department. “If they shared the data, the public would realize this is not a once-in-a-blue-moon event,” says Owens. “This happens more than they think.”

Fire Commissioner Derrick Sawyer has been dealing with the issue of cardiac arrest for years: As commissioner, he oversees Philadelphia’s EMS system. He has no future plans to release the CARES data. “Not currently,” he says. When asked to explain why Philly’s survival rates are significantly lower than those nationwide, Sawyer says, “I have not had the opportunity to specifically study the issues surrounding cardiac arrest, therefore I cannot provide answers.” He concedes the numbers are problematic, though. “We realize that we don’t meet the national average.”

On May 23rd, Sawyer will vacate his post, leaving the issue to Adam Thiel, a former Virginia fire chief appointed by Mayor Jim Kenney to lead the department. When asked how he plans to address Philly’s cardiac arrest problem, a mayor’s spokeswoman spoke on Thiel’s behalf: “He feels like he would need to speak to more folks in PFD and in City Hall … in order to answer adequately.”

Studies show that it’s not uncommon for cardiac arrest survival rates to vary widely from community to community. But experts agree that proactive, preventative measures can be taken to improve outcomes, and that starts with teaching the public about how to respond in emergency situations.

•

Victims of cardiac arrest often collapse with little or no warning, and their odds of survival decrease with every minute that passes following an attack. The swift intervention of bystanders can be the difference between life and death.

To adequately help a person suffering from cardiac arrest, a witness not only needs to dial 911, but also must know how to administer CPR and use a defibrillator when necessary. In Philadelphia, only 20.4 percent of cardiac arrest victims who are considered potentially revivable and found by bystanders survive. The national survival rate is 33.7 percent.

Dr. Benjamin Abella is the clinical research director at Penn Medicine’s Center for Resuscitation Science. Early CPR delivery can double — or even triple — a person’s shot at survival, he says.

But here’s the problem: Philadelphians are either ill-equipped or unwilling to perform CPR. According to CARES data, bystanders only intervened using CPR in 14.4 percent of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in 2015. That’s compared to a national average of 39.8 — more than twice Philly’s rate.

Former Philly Fire paramedic Joe Russell is the executive director of the CPAT Network, a nonprofit focused on emergency response training and awareness. He points out that according to recent studies, individuals living in low-income neighborhoods and majority African-American or Latino neighborhoods are more likely to suffer out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and less likely to receive CPR than those in wealthier, whiter areas. “The cost of training, time required, and lack of non-English training are commonly cited reasons for why people do not learn CPR. Fear of disease transmission from mouth-to-mouth breathing, doing it incorrectly, or legal action from being unsuccessful may be reasons why people do not perform CPR,” researchers affiliated with the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado wrote.

“We must not be afraid to address disparities affecting our minorities and those that are economically disadvantaged,” Russell says. Commissioner Sawyer declined to comment on the disparity.

Philadelphians are similarly unprepared to use defibrillators. When asked what they would do in a hypothetical situation where they encountered someone experiencing sudden cardiac arrest, less than 10 percent of people polled in Suburban Station and Market East Station mentioned defibrillators. One-third of participants couldn’t identify the devices, and a whopping 60 percent didn’t know that they could be used by non-medical personnel. (For more information on emergency response and to sign up for training, visit the Red Cross’s website.)

Then there’s the issue of access: In 2012, a team of Penn Med-led volunteers found just 900 publicly accessible defibrillators scattered throughout the city. The devices are required in federal buildings, but not in municipal ones. And while defibrillators are recommended in schools, they’re not required there either. They also don’t come cheap, costing somewhere between $1,200 and $2,500 apiece — that’s a pretty penny for Philly’s cash-strapped schools.

“There’s not a coordinated, citywide effort for this,” says Abella, “and that’s a problem.”

To make matters worse, explains Dr. Raina Merchant, the assistant professor at Penn Med who conducted the defibrillator survey, some of the machines sit behind glass cases that read “For trained professionals only,” despite the fact that they can be used by anyone. Understandably, the label causes confusion and can dissuade people from using defibrillators during a crisis.

When it comes to bystander response, a lot of public spaces “go halfway,” Abella says. “They buy [a defibrillator], they slap it on the wall. Okay, that’s good. But what then?”

While Abella says a bystander’s response (or lack thereof) is the No. 1 factor that determines whether a cardiac arrest victim lives or dies, he also argues that an area’s EMS bears some responsibility for their fate. The sooner paramedics arrive on the scene, the more likely a person suffering an attack will survive.

Since 2010, the Philadelphia Fire Department has fallen short of its goal of getting to emergencies within 9 minutes 90 percent of the time, according to city data. “Philly has so many EMS calls,” says Abella. “Those poor guys — there aren’t enough medic units on the streets for all the calls they get.”

Determining what makes one EMS system more efficient than another is tricky. To this day, researchers and professionals disagree about best practices. There’s no consensus, for example, about whether hiring more paramedics improves a city’s survival rates. To speed up the Philly EMS’s lagging response times, Sawyer says the department created a community risk reduction unit in 2015 that directs paramedics’ attention toward the most urgent calls. He also says that the department has plans to increase the number of medic units it has in service, though he wouldn’t specify when.

•

CPAT Network’s Russell says Commissioner Sawyer has been sitting for months on an idea that could save the lives of cardiac arrest victims.

Last November, Russell introduced the fire department to the American Heart Association-endorsed PulsePoint, which alerts CPR-trained individuals to sudden cardiac arrests in their vicinity and directs them to nearby defibrillators. According to our reporting, there are no other apps in the country that provide this service.

The tool has been implemented, with support from local EMS departments, in about 1,500 communities in 25 states across the country, including Los Angeles and Burlington County, New Jersey. Research published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a nearly identical app — this one built for the study and tested in Sweden — was associated with an increase in bystanders initiating CPR.

But according to emails obtained by Philadelphia magazine, Sawyer has refused to provide Russell with the letter of support for the program that he says he needs. The letter, Russell says, is necessary for getting funding from donors outside of city government. (In most of the big cities already using PulsePoint, hospitals, nonprofits and businesses have underwritten a significant portion of the costs). The app will cost an estimated $10,000 upfront and $18,000 annually to maintain, money that will go toward installing software in Philly’s EMS dispatch system, as well as yearly licensing fees.

“We are asking for your support to help get the financial support, so we can have PulsePoint implemented here in Philadelphia,” Russell wrote to Sawyer on March 26. He proceeded to ask the commissioner for a vote of confidence: “A letter of support from you will help us to get the necessary funding to start and maintain the project going forward. … Philadelphia’s current cardiac arrest survival rate should not be ignored. Should we continue to do what we did yesterday, or should we give a program like PulsePoint a chance?”

Sawyer wrote back, “With all due respect, why would I support a project that is not funded? Once you can provide me with evidence that your project is funded … I will gladly write a letter of support.”

When asked about PulsePoint moving forward, the commissioner showed no sign of budging. “My plans are zero,” he says. “We’re not going to carry the ball for [Russell]. … I’m not his pimp. He can’t use my name to get money.”

So the project hangs in limbo: Russell says he needs Sawyer’s help, and Sawyer won’t give his support until he sees the money.

There are a handful of other efforts underway to address Philadelphia’s low rates of survival from cardiac arrest, though. Sawyer says the Fire Department, Penn Med and Independence Blue Cross are organizing a citywide CPR training initiative for the public. (City government already funds CPR and defibrillator training for municipal workers.) There are also bills pending in the Pennsylvania House and Senate that would mandate emergency training for all high school students.

For the loved ones of Ryan Gillyard and Danny Rumph, these programs can’t be implemented soon enough. Monday marked the one-year anniversary of Gillyard’s death. The Gillyard family’s pastor led an evening mass at St. Denis Church in Havertown, where Gillyard attended middle school, and where he’s now buried.

Father Gallagher can see the teenager’s grave from his kitchen window. He sees when Gillyard’s former classmates pass by his memorial, and when they stop in their tracks to pray. Every once in a while, they’ll lean down, scoop up the football that graces the headstone, and give it a toss. “They haven’t forgotten,” he says.

Follow @zrkirsch and @emmajanepettit on Twitter.