Philly’s Most Walkable Areas Are Also Its Whitest

What's behind the race gap?

Safer streets, higher property values, lower transportation costs — these are just a few of the benefits of living in a walkable neighborhood.

It’s no wonder that urbanism writers have touted Philadelphia’s ranking as the fourth-most walkable big city in the country, and Mayor Michael Nutter has signed a “Complete Streets” executive order.

But in Philly and other cities, the gains of walkability have not been realized by everyone.

Take San Francisco, for example. It’s the second-most walkable city in the country. However, a new study out of California Polytechnic State University shows that the city’s most walkable neighborhoods are also among its whitest.

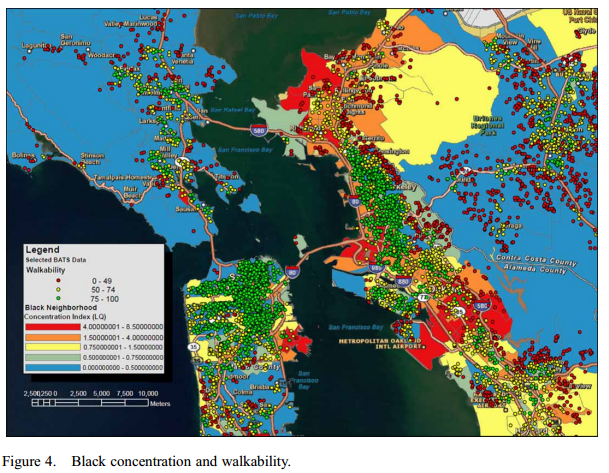

To illustrate, the study overlaid a map showing concentrations of black residents throughout San Francisco (the red areas below are predominately African-American neighborhoods), with dots marking the various degrees of walkability in an area, using the company WalkScore‘s range of 0 to 100. On the map below, green dots indicate high walkability (scores of 75-100); yellow dots show semi-walkable neighborhoods (50-74), and red dots represent the least walkable neighborhoods. As you can see, the predominately black neighborhoods have quite a small share of green dots.

To no one’s surprise, those areas with the highest degree of walkability are also some of the most central and affluent parts of town — such as San Mateo and Berkeley.

WalkScore’s ratings are determined by walking routes, the friendless of pedestrians and other metrics.

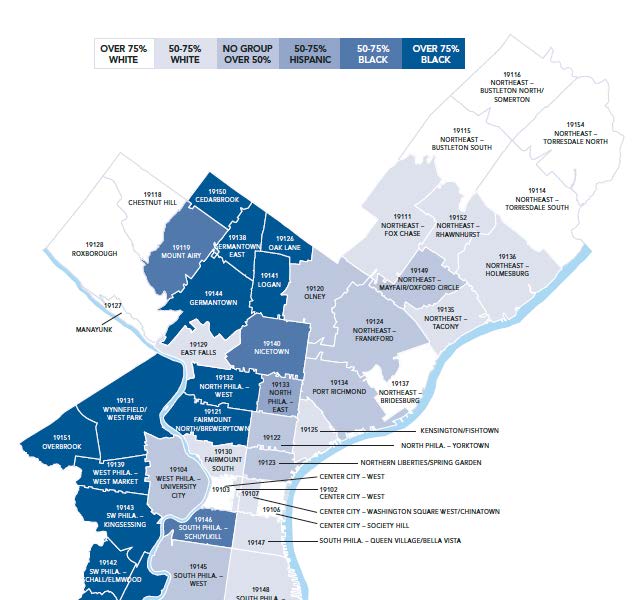

In Philly, similar divisions of race and walkability are apparent when you look at the city’s WalkScore measurements. There’s a 10- to 15-point gap in the walkability scores of majority-black areas such as Brewerytown, Kingsessing and North Philly (west of Broad, south of York), compared with whiter neighborhoods such as Northern Liberties, Bella Vista and Society Hill. And much like San Francisco, the inner pocket of Center City is simultaneously a zone of near-perfect walkability and one of the whitest parts of town.

That’s not to say heavily black neighborhoods are not walkable — just less so, compared to neighborhoods at a similar (or greater) distance from Center City that have more white residents. For example, Powelton Village still has walkability scores hovering in the high 80s and low 90s (which are better than the citywide average). But it’s not as walkable as the whiter area in South Philly between Passyunk and Moyamensing avenues.

Perhaps these trends are less correlated with race and more with long-running discriminatory housing practices in cities across the country. It’s well-known that black Philadelphians have been pushed out of supremely walkable downtown areas over time, moving from Center City into North and West Philly.

Racial Distribution of Philly Neighborhoods. Source: Pew 2013 State of the City Report

Although historical factors play a part, the study’s author says the connection between race and walkability is not coincidental:

The most notable finding is that — when controlling for factors like housing attributes, proximity to transit, and access to a car, with the exception of Asians — minorities tend to live in less walkable locations. … When blacks live in a neighbourhood that is predominantly black, neighborhood walkability declines even more.

What the study suggests — through data and qualitative interviews — is that the lower concentration of black residents in San Francisco’s walkable areas is due not only to prohibitive costs of living, but also sociocultural factors that pull blacks toward those neighborhoods. Individual preferences for being close to certain businesses and institutions — “many individuals spent more time talking about social places like barbershops and manicure salons than they did about price,” the author writes — draw minorities toward less-walkable areas.

These preferences, combined with the legacy of historic discriminatory practices, create a situation where social and racial barriers are magnified as parts of central cities are abandoned, with minorities unable to afford or choosing not to live in the walkable city and driven out to more car-dependent suburban locations; those who do remain are forced into areas that are less walkable.

It’s worth noting that according to WalkScore, the further out you get from Center City, the more equitable walkability becomes in Philly. There’s little difference between the scores of Manayunk and Overbrook, and virtually no difference at all between Germantown and East Falls (each duo of neighborhoods having starkly different racial makeups).

Whether or not the study’s conclusions about minority residents selecting less-walkable places to live are consistent in Philly (or even true on a large scale, given the small sample size of interviews), it underlines the importance of including topics such as privilege, racial segregation and social equity into any discussion of urban development.