13 Things You Might Not Know About the Pine Barrens

They’re big, they’re wet, and they’re weird. Oh, and they’ve got their own monster!

Pine Barrens | Jim Lukach via CC BY 2.0

Today is National New Jersey Day, which is a pretty peculiar thing for a day to be. We thought about celebrating by driving around a traffic circle a few times. Or maybe going to a mall. Or having somebody else pump our gas! Instead, we decided to find out more about one of our region’s most remarkable features: the Pine Barrens. Most of us only know the Pine Barrens as that wasteland we drive past on our way to the Shore. But push a little deeper in, as John McPhee did in his 1967 book The Pine Barrens, and you’ll uncover a whole weird world. Here, a compendium of lore about our very own local wilderness.

1. The 1.1-million-acre Pinelands Natural Reserve stretches south and west from northern Ocean County and makes up 22 percent of New Jersey’s total land mass. Created by Congress in 1978, the reserve was designated an International Biosphere Reserve in 1988. It’s bigger than either Yosemite or Grand Canyon national park.

2. European settlers found the sandy, acidic soil unsuited to farming and left the land largely untouched, but beneath the pines lies a natural reservoir of bacterially sterile, chemically pure H2o that the U.S. Geological Survey has compared to “uncontaminated rain-water or melted glacial ice.” This water, tinted like tea from tannins from cedar trees and iron from the ground, was once prized by sea captains to take along on voyages because it stayed potable longer than any other water.

Via Popular Science Monthly Volume 85, Public Domain

3. Early “Pineys,” as Barrens residents call themselves, included Quakers who’d been expelled from their meetings for fighting in the Revolution; outlaws and smugglers; and Tory loyalists known as the Refugees who, despite their politics, rode in packs and killed and robbed indiscriminately.

4. The Barrens became home to several industries in the course of their history, including charcoal-making, glass-making (the first Mason jar was made here), woodcutting and cabinetry. Benjamin Randolph, a cabinetmaker in Speedwell, crafted the writing desk at which Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence.

5. During the American Revolution, highly absorbent sphagnum moss gathered from the Barrens stood in when needed for cloth bandages, and in later years, it was packed into florists’ boxes as protection for the blossoms inside.

6. In the late 1800s, Joseph Wharton, the industrialist for whom Penn’s Wharton School is named, acquired a hundred thousand acres of Pine Barrens land. He planned to transport the water they contained via canals to a vast reservoir in Camden, then run it beneath the Delaware River into Philadelphia, so he could replace the city’s foul drinking water with this pristine source. Alas, the New Jersey legislature thwarted him by prohibiting the export of water; his land now makes up the Wharton State Forest.

By PhreddieH3 at English Wikipedia, Public Domain

7. In 1911, Elizabeth C. White, daughter of a cranberry grower in the Barrens, began to experiment with crossing the wild blueberries that grew there with larger commercial varieties. After decades of work, she reportedly grew blueberries the size of baseballs. In 1951, she invited landscape designers from the state highway department to tour her fields and tried to convince them to plant blueberry bushes along the Garden State Parkway — which they eventually did.

8. In 1913, a researcher named Elizabeth Kite published a report called “The Pineys” that included tales of heavy drinking, livestock quartered in children’s bedrooms, incest and widespread inbreeding. The report caused a scandal, and the governor of New Jersey, James T. Fielder, visited the Barrens, then asked the legislature to isolate the area from the rest of the state. He called the residents “a serious menace” to the public: “They have inbred, and led lawless and scandalous lives, till they have become a race of imbeciles, criminals and defectives.” In later years, Kite told an interviewer, “Nothing would give me greater pleasure than to correct the idea that has unfortunately been given by the newspapers regarding the pines. … I think it is a most terrible calamity that the newspapers publicly took the term and gave it the degenerate sting.”

9. In the 1920s, housing lots in the Pine Barrens were given away as free gifts for every new subscription to a Philadelphia newspaper, and during the Depression, deeds were given out as door prizes at movie theaters. At the time, the land cost five dollars per lot. Developers would hang fruit from the limbs of the pine trees and position fishermen in boats with dead fish on their lines to entice buyers.

10. Despite all that water, fire is a constant threat in the Pine Barrens. In July 1954, in the midst of a drought, what became known as the Chatsworth Fire started in a cedar swamp and burned 19,500 acres. In 1965, a policeman in the Barrens set 69 fires and called them all in on his police radio. After his arrest, he was unable to explain why he’d done it. In 2015, a fire started by carelessly discarded charcoal briquettes burned 1,000 acres.

11. In the 1960s, the Pinelands Regional Planning Board floated a proposal for a supersonic jetport in the Barrens that would have been the largest on earth: “four times as large as Newark Airport, LaGuardia and Kennedy put together,” according to McPhee. It would have brought passengers from Paris in 90 minutes; high-speed trains from its terminals would have reached Philadelphia in 20 minutes and New York City in half an hour. It also would have eaten up 32,000 acres of land and devoured an entire state forest, several ponds and a lake. It never got off the ground.

12. In the 37th episode of The Sopranos, Paulie and Christopher get lost in the Barrens after trying to bury Russian mobster Valery there, and Tony has to rescue them.

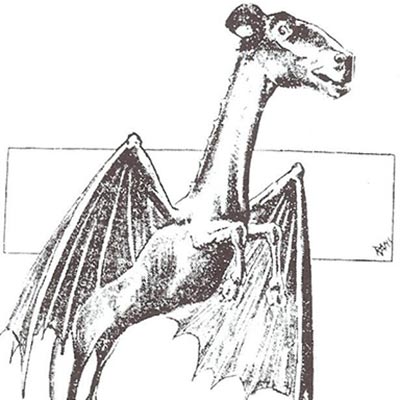

Drawing of the Jersey Devil as published in the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1909, Public Domain.

13. By far the most famous resident of the Pine Barrens is the Jersey Devil, a.k.a. Leeds’ Devil. In case you’re disinclined to believe in a creature with a goat’s head, the wings of a bat, cloven hooves and a forked tail, consider this: Native Americans called the Pine Barrens “Popuessing,” or “place of the dragon,” and Swedish explorers dubbed them “Drake Kill,” meaning “dragon river.” Those who claimed to have viewed the monster include Joseph Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon; Commodore Stephen Decatur; and hundreds of common citizens in the week of January 16th through 23rd, 1909, as faithfully reported by newspapers at the time. The resultant panic closed schools and businesses, and the Philadelphia Zoo offered a $10,000 reward for a sample of the creature’s excrement.

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.