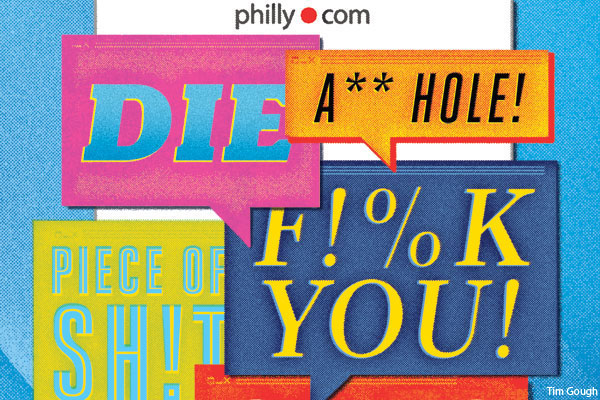

Philly.com’s Commenters Are More Vile Than You Think

Last February, Philly.com posted a heartwarming story, also published in the print edition of the Daily News, about a North Philly peewee basketball team that needed to raise $11,000 to get to the International Small Fry Basketball Tournament in Orlando. The community rallied to pony up the money. Online, the story garnered this insightful comment:

YOUR ARE LOOKING AT THE GRATERFORD CLASS OF 2020. — LARRY CHESWALD

Classy, Larry.

A May story about Eagles owner Jeff Lurie’s second marriage, to Tina Lai, who is Vietnamese, brought this illuminating thought:

SHE HAD HIM AT ‘ME LOVE YOU LONG TIME.’ — Unknown

A story about a black bus driver arrested for trying to kidnap a child in Delco garnered this bon mot:

A VERY HAPPY BLACK HISTORY MONTH TO ALL!!!!! — cynic al

And a story set in West Philly resulted in this doozy:

BRING IN WILSON GOODE TO DROP A BOMB OVER THAT ENTIRE COMMUNITY. INSTEAD OF MLK DAY WE SHOULD CELEBRATE WILSON GOODE BECAUSE THAT WAS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL THING I COULD THINK OF … HE IS MY HERO AND WOLD VOTE FOR HIM AGAIN. A TRUE PATRIOT! — Friend to All

As any perusal of old editorial cartoons will attest, distasteful discourse has always been a part of the American conversation. It’s the price you pay for free speech—some of that speech is bound to be awful. But the Internet has been a game-changer in the hate-speech sweepstakes, allowing anyone to instantly comment on just about anything. The online-comments sections of major metropolitan newspapers have become magnets for racists, sociopaths and assorted trolls, who every day deface the walls of award-winning reportage with their graffiti of ignorance and intolerance.

Then there is the comments section of Philly.com.

To quote Obi-Wan Kenobi: Nowhere will you find “a more wretched hive of scum and villainy.” On a good day, it’s bad. On a bad day, it’s vile.

There are a lot of bad days on Philly.com.

“Philly has a reputation for being a crass community, doesn’t it?” understates Kelly McBride, an expert in media ethics at the Poynter Institute, a highly respected journalism think tank that more or less serves as the conscience of the industry. “That’s the thing about comments sections: They hold up a mirror to the community and reflect back the good parts as well as the parts that you just don’t find very attractive.”

She’s being kind. A better way to put it might be: Is the city really this full of hateful, horrible people? And even more sobering: What kind of “civic dialogue” is Philadelphia reflecting to the world?

Earlier this year, the Inquirer and Daily News both went behind paywalls, meaning (in theory, at least) that only people who paid for access to the sites would be able to comment on stories posted there. But many of the papers’ most juicy, gossipy and sensational pieces—i.e., the ones most likely to invite comment—are still put up for free at the umbrella Philly.com site. And the comments section on Philly.com remains the Wild West.

The reason is obvious: People can comment anonymously. Anonymity breeds contempt. It subverts the social compact that keeps polite society reasonably so: We know who you are, and you will be held accountable for your actions. But at the dawn of the World Wide Web, the hierarchy of the newspaper industry was comprised of old gray men out of their depth when it came to “the Internets,” making it ridiculously easy for techie whiz kids to convince them of the necessity for anonymity in comments. “Early on, the Internet felt very much like a fraternity house,” says McBride. “Twenty-something guys were running it, and they told us that this was the way we had to do it.”

The enormity of this mistake cannot be overstated. Anonymity has proven to be soundly counterproductive to journalism’s prime directive: to shine disinfecting sunlight upon the dirty deeds that lurk in society’s darker corners. It has allowed lunatics to float about in the clouds of cyberspace like phantoms, lashing out like spoiled (and often racist) children without a trace of accountability.

CABS SHOULDN’T PICK UP BLACK PEOPLE — Philly54321

Unlike the bar one must get over to have a letter to the editor published in the print versions of the Inquirer and Daily News—which require a name, an address, and a phone number that’s called to verify the author’s identity—all it takes to start commenting on Philly.com is a screen name and a working email address. This relatively lax system, combined with the sheer volume of comments on Philly.com—upwards of 50,000 a month—has resulted in a perfect storm of poisonous exegesis that has:

- Driven out any and all reasonable people who might have something constructive to add to the public dialogue the spaces were designed to foster. Want proof? Scroll down to the bottom of pretty much any article on Philly.com. The Algonquin Round Table this ain’t.

- Demonstrably damaged the brand of Philly.com/Inquirer/Daily News as the region’s most trusted source of news and information. A scientific study recently published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication found that these toxic opinions can negatively impact readers’ capacity to process the information in the actual article being commented on.

- Unwittingly turned over the biggest soapbox in the Philadelphia online media market—90 million page views a month—to a small band of all-purpose h aters, bigots and trolls who routinely inject into the public sphere the type of shocking invective long banished from mass media in this country.

Here’s the rub: It didn’t have to be like this.

If any of the various owners of Philly.com since its inception in 1995 had allocated the necessary resources (such as, oh, enough people to monitor the thing), the wild and woolly comments section could have been tamed a long time ago. But in 2009, just around the time it was becoming apparent that the comments section was fast turning into an idiocracy, the Great Recession was gaining steam. The newspaper industry was unraveling; at the Inquirer and Daily News, corporate energy and resources were focused on a desperate search for new revenue sources, at the same time that staffs were being reduced through layoffs. Not only was nobody watching the store—there was no one to watch the store.

“The simple fact is, user comments weren’t the biggest challenge we faced,” says Ryan Davis, who served as Philly.com’s president from October 2009 to October 2010. “Fixing the comments wasn’t going to suddenly make us more money that we could use to support more journalism. Fixing the comments wasn’t suddenly going to get us more advertising. Fixing the comments wasn’t going to create a new business model that would show us the path forward. So it was not at the top of the priority list. But at the same time, every time I came to the site, I would log on and see something that bothered me. Every time, without fail.”

Most Newspapers began rolling out online commentary in the early aughts, but by the mid-aughts, the jury was still out among the ranks of the ink-stained wretches as to whether allowing readers to comment directly on online pieces was good civics or just an invitation for crazy-ass ravings. “There was a conversation in the industry five or six years ago about whether or not comments were a good thing, and for the most part, that issue is settled. For the most part, journalists believe that comments are a good thing,” says the Poynter Institute’s McBride. “With the rise of social media, the audience expects to be able to interact with the news they consume.”

Reader commenting on Philly.com has also been around since the late ’90s, but it wasn’t until 2008, following years of internal deliberations and successive regime changes, that the site went all-in and began allowing readers to talk back at the bottom of every article. “Journalism had been a one-way conversation for too long,” says one Philly.com staffer. “It was a good idea to open the door and allow the public to start commenting on our work.”

Well, on paper, maybe. In practice? Not so much. There was some recognition from the get-go that there was going to have to be policing of the comments, to keep salty language out. The front door of Philly.com is guarded by a word filter—like a bouncer at a fancy nightclub—that bars entry to commentary containing the obvious objectionables: curse words, racial slurs, crude pornographic euphemisms, “hundreds and hundreds of words and phrases, some of which I’d never even heard before,” in the words of one former Philly.com staffer. But Philadelphians have ample talent for being shockingly offensive without the help of the F-bomb and the N-word.

“Every now and then,” says another former Philly.com staffer, “we would get a call from the big bosses asking us to delete this or that offensive comment. One time we got a call from [former owner Brian] Tierney wanting to know why there was a comment up on the site that mentioned his wife by name and a reference to ‘ATM.’ We were like, ‘Okay, who’s going to tell Brian Tierney what ATM stands for?’” (Google it.)

The only way to guarantee that no offensive reader comments go up is to have human moderators monitor each and every one. Philly.com averages one new comment a minute.

One option is to do what the San Francisco Chronicle, NPR, the Boston Globe and the Gannett chain have done: outsource comment moderation to companies like eModeration and ICUC, which can charge upwards of $40 an hour ($350,000 a year) for 24/7 moderation—a necessity, given that the worst comments invariably arrive in the dead of night.

Thus far, that’s a road Philly.com hasn’t elected to take. Instead, it continues to rely largely on readers to flag objectionable stuff. The downside is that heinous comments can remain on the site, in full public view, for hours, days, even weeks, before disappearing. Moderating the comments on a news portal fed by two city newspapers is a bit like trying to lifeguard a hundred shark-infested pools at the same time. And as the old Pink Floyd song goes, every day the paperboy brings more.

Back in 2007, Philly.com’s Web traffic—then roughly 1.5 million unique visitors per month—was less than that of NBC 10’s website; by 2009, Philly.com had more than tripled its guests. From 2009 to 2010, it was rated by Nielsen to be the fastest-growing news site in the country. The volume of comments exploded as well: from a thousand a month to a staggering 50,000.

“The idea was to create a community where there could be an active and lively discourse,” says Yoni Greenbaum, who served as vice president and general manager, digital, from 2010 to 2012 at the Philadelphia Media Network, once the parent company of Philly.com, the Inquirer and Daily News. “What we got instead was a cesspool.”

There is a lot of offensive commentary on Philly.com—cranky diatribes, ad hominem attacks on other commenters. But the bulk is racially charged, if not straight-up stone-cold racist. The infamy of Philly.com’s race-baiting extends far beyond the city limits: Much like Philly sports fans, the comments section at Philly.com has a well-earned national rep for being among the worst of the worst—which, when you read the bile in the comments sections of other newspapers, is really saying something.

The Daily News’s Will Bunch has weathered his share of abusive comments on Attytood, his popular left-leaning blog. He thinks the endemic racism of so many Philly.com commenters is merely a 21st-century extension of the fear-based racial animus that’s been dividing, and depleting, the city since the 1950s.

“In Philadelphia, you have this whole city-vs.-suburban thing,” he says. “Over the course of a couple of generations, we’ve gone from a city of two million people and kind of smaller suburbs to white flight and ballooning suburbs populated by a lot of people who used to live in the city and are still rationalizing why they left. You know: ‘We left to get away from those animals, those savages,’ or whatever. It’s hard to believe that 60 years later, it’s still being fought out. It’s not being fought out in the streets anymore. It’s being fought in the Philly.com comments section.”

MARVIN HOLMES EH. LEMME GUESS, HE PRONOUNCES “EARTH” AS “URFF.” — Norma Stitz

The unceasing deluge of septic dialogue—as many as 10 people a day are banned from ever posting again—has taken a psychic toll on Philly.com staffers. “We were very proud of the journalism that the Inquirer and Daily News were producing,” says one former Philly.commer. “To have that constantly undermined by people being assholes on our website every day, day after day, was soul-crushing.”

More than a hundred years after W.E.B. Du Bois published The Philadelphia Negro, a pioneering sociological study of the city’s African-Americans, race relations here—at least as reflected on the message boards—don’t appear to have come very far. The sad truth is that Philly.com is merely holding up a mirror. Neither Interstate General Media, which currently owns the Inquirer, the Daily News and Philly.com, nor Lexie Norcross, the daughter of Interstate co-owner and political kingmaker George Norcross, and the woman who oversees Philly.com, would agree to be interviewed for this piece—ironic in a story about commenting. Through a spokesperson, the company did offer vague promises that it would be unveiling a new “comments experience” in the coming months that will rid the site of the malignant verbiage catalogued here.

Maybe they’ll pull up the drawbridge—turn off reader commentary altogether. Ironically, this is exactly the course of action that Philly.com super-commenter Jim Dolan advocates in his darkest hours, when the nattering nabobs of negativity finally break his irrepressible will to comment—something he has done, by his own calculation, more than 400 times over the past dozen years.

“The comments section is a love/hate thing for me, because there are times when it just leaves a really bad taste in your mouth about what Philadelphia is about,” says the 53-year-old Havertown native and IT professional, who now resides in Apopka, Florida. “It could be the happiest story in the world and somebody always has something negative to say. Even though I comment all the time, some days I wish there was no comments section.”

He’s not alone in wishing for that—or for a more constructive dialogue that might actually move the city forward. From last February:

I HAD A DREAM LAST NIGHT THAT I READ AN ARTICLE ON PHILLY.COM AND ALL THE COMMENTS WERE POSITIVE. — philly57