Garrett Getlin Snider Is Not Your Average Teenager

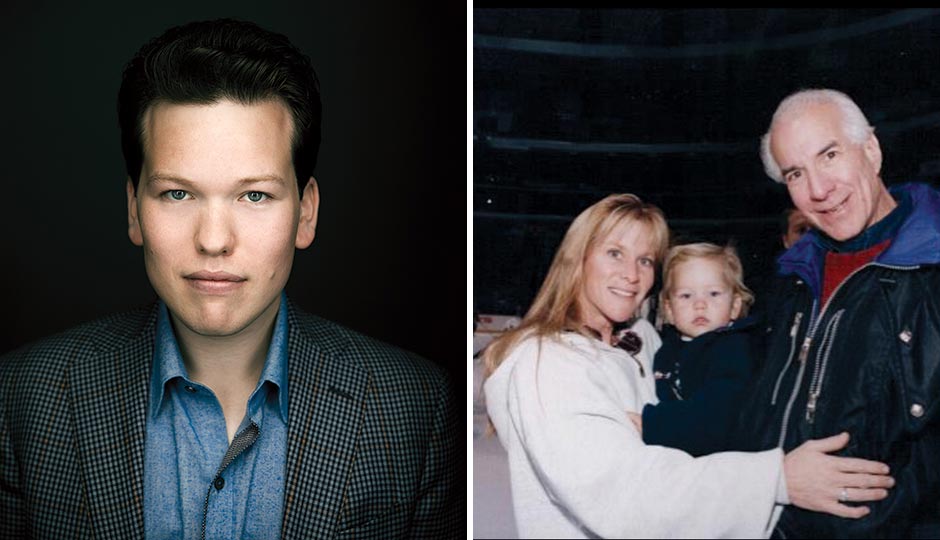

Left: Garrett Getlin Snider (photography by Justin James Muir). Right: Lindy, Garrett, and Ed Snider, circa 1997 (courtesy of Garrett Getlin Snider)

Garrett Getlin Snider is fretting.

This really isn’t so unusual, as it turns out. Garrett Getlin Snider frets a lot. About his twin sisters, “16 and gorgeous,” who are now at an age where every horny teenage boy on the Main Line is taking notice. About his grandfather, Ed Snider, the legendary 82-year-old Philadelphia Flyers owner and chairman of Comcast Spectacor. About his grandmother, about his studies at Drexel, about the kids: the kids in Montgomery County, the kids around the country, the kids around the world. Who is going to help the kids? And so Garrett Getlin Snider frets, worry lines already beginning to form across his square, pale 19-year-old face.

Tonight the fretting concerns a fund-raiser, because Garrett Getlin Snider is constantly raising money for some good cause. He’s here at the Black Box space inside the Prince Theater on Chestnut Street hosting a screening of Fed Up, the Katie Couric-narrated documentary on how bad food is killing our kids. The theater has been set up to accommodate a hundred, and 75 tickets have been sold, but so far, just a few minutes before the film is set to unspool, there are only a dozen people milling about. Clutching a clipboard and looking, well, fretful, Garrett shrugs. “This is the problem when you only charge a nominal donation,” he says. “People RSVP and don’t show. I don’t know … ” He looks around, as if willing more guests off the elevator. “We’ll have to see if we’re still going ahead.”

The crowd may be small, but it’s composed of the Right People: coffee guru Todd Carmichael (co-hosting), and starry restaurateur Marc Vetri and his business partner Jeff Benjamin, who do a considerable amount of charity work with Garrett. Reality-star-turned-Rittenhouse-socialite Erin Elmore and her hunky husband, tech CEO Craig Spitzer, are here, as are chef Hope Cohen and psychologist Judith Sills, as are both film-office diva Sharon Pinkenson and her hair. In the end, 22 people show up, and the show goes on and the money is raised and on their way out the attendees hug Garrett and tell him what a great job he did and how proud they are and how important this is and Honey, call me!

“I have never met anyone in my life,” Abbie Newman, the executive director of East Norriton’s Mission Kids Child Advocacy Center, will tell me later, “who has a bigger heart than Garrett.”

Richard Vague, the venture capitalist, goes one better. “Frankly,” he says, “I wish the world had more Garretts.”

WITH HIS waxy complexion, pale as a bedsheet, and Byronic air, Garrett Snider sometimes seems like a young man who’s just jumped out of a 17th-century Flemish painting. There’s something intrinsically delicate about him, as if he’s made of Wedgwood and might shatter into pieces if he fell. While his overall look is striking in a gothic sort of way, it’s how he speaks — the slow cadence, the big words, the long, pontifical sentences, all delivered with just a trace of Oy gevalt! — that really raises eyebrows. In conversation, he comes off like a cross between Encyclopedia Brown and a canasta-playing yenta from Boca named Estelle.

He’s a child from a broken home who’s obsessed with the concept of family, a 19-year-old with the affect of George Plimpton, a college kid with seemingly few, if any, close college-age friends, a fey young man with a handshake that could break your wrist. The witty scion of one of the most high-profile families in Philadelphia, he has donated countless hours to worthy causes while his contemporaries ditch classes to play beer pong. He’s an enigma everyone tries to figure out and no one can. And he just might be Philadelphia’s next great philanthropist.

While other college freshmen are choosing majors, Garrett Snider is organizing charity events — he launched his own foundation at age 10 — and occupying a singular space in the city’s fund-raising circles. A philanthropic soul, he’s rotating through a world of old money and power, which is both inspiring and more than a little weird. He’s a focused and determined advocate for social justice for children, in the way people who write checks and attend lots of black-tie galas for such causes are. Only Garrett is a teenager, and doesn’t write checks, and his circle of friends seems comprised almost exclusively of people older than his parents.

In short, you’ve never met a 19-year-old like this. You certainly weren’t a 19-year-old like this. “We used to always joke that he was four going on 40,” says his mother, Lindy Lou Snider. “He was born an adult.”

Lindy is Ed Snider’s daughter, and that alone has made Garrett more than just your average young civic-minded socialite; he’s got royal Philly blood running through his veins. That fact has hardly been lost on Garrett, who in 2014 legally changed his name from “Garrett Cole Getlin” to “ Garrett Getlin Snider,” the better to reflect his place in the Snider dynasty — and provide ammo to gossips who say he’s less interested in helping kids than in raising his own profile. (Fueling this fire: He’s also close friends with one of the city’s most high-profile publicists, who helps propel Garrett and his causes.) “I’ve had to deal with that critique,” he acknowledges. “A lot of people have said that to my face. It’s an open dialogue to have. At the end of the day, we’re a family. And that’s what it is.”

As both a Snider and the person who’s always two generations younger than everyone else at the party, Garrett tends to attract a lot of attention in Philly high society. He knows a lot of people don’t get him, but he’s used to that. When he was growing up, other kids didn’t get him, either. “I was definitely thought of by my peers in my younger years as kind of my own population,” he says. “You know what I mean?”

Which raises the question: Is Garrett Getlin Snider a singular, selfless role model for the maligned millennial generation, the Ultimate Nice Jewish Boy? Or is he a young man who spends his time air-kissing and hopscotching his way through every gala in town to live up to his image as The Talented Mr. Snider?

HE HAD A posh childhood, packed with all the amenities one would expect to come with Snider lineage, but he didn’t have a particularly happy one. Actually, it appears he didn’t have a childhood at all.

His first dive into the world of charity came at age nine, when, seeing the destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina, he turned to his mother and asked if his upcoming birthday party could be flipped into a fund-raiser for the victims. As an adolescent, he volunteered at Lankenau Medical Center and the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center. At 13, while working in a soup kitchen, he became appalled by the condescension with which the homeless were treated and partnered with a local priest to develop new guidelines for volunteers at food banks and churches to, in his words, “instill some dignity.” When he’s not at Drexel, where he’s a first-year communications major, he volunteers at CHOP (with kids whose parents are in prison) and at First Star, a program that helps prep foster kids for college. Following a charity fashion show at Saks Fifth Avenue in Bala Cynwyd in 2012, Randi Edelman, the store’s marketing director, met Garrett, then 16, who had been one of the models. “At the end of the event, he came up to me in a way you would never expect someone his age to and thanked me for how I treated him,” Edelman recalls. “He was saying I was so helpful and so nice and ‘If I can do anything for you, let me know.’ I had no idea who he was.”

Indeed, he has become an omnipresent if outlying face at charity events favored by the graying, deep-pocketed crowds of Philadelphia benevolence — a peach-skinned cherub amid the balding men in tuxes and bejeweled women in chinchilla. From the start, the staples of the city’s society-fete circuit knew two things: He was Ed Snider’s grandson, and he was different from any child they had ever seen. His vocabulary was deep; his grammar was flawless; he could converse about current events with the alacrity of a college professor. “I remember meeting him when he was just this little kid,” says Todd Carmichael, “and thinking, What the fuck?”

The one person who didn’t find any of this strange was Garrett. “The only thing I knew was that I was thinking about my happiness and the happiness of the people around me on a conscious level more than the kids around me were,” he tells me one night over a meal of chicken parmigiana at Dante & Luigi’s in Bella Vista. “I always took responsibility for my own happiness. When I got caught up in the tumult of [my parents’] separation, which was really movie-worthy, I would be sad. I would be sad a lot. Finally, around 11 or 12, I started thinking to myself about how I was going to manage my moods. As a result, I trained my brain. I am in complete control of my emotions.”

His precocity (on steroids) has made him a darling among the ladies who brunch, who, in the words of one of his younger friends (she’s under 40), “treat him like he’s a 30-year-old gay man. He’s not.” “He is the most social person I know,” says Flyers songstress Lauren Hart, who is BFFs with his mother. “He puts me to shame every time I look at his Facebook page.”

Ah, yes, Facebook. Proof of the stunning speed of Garrett Getlin Snider’s rise in beneficent circles can be found in his social media. His 2,594 Facebook friends include names from the worlds of food (Vetri, Susanna Foo, Audrey Claire Taichman), media (Lexie Norcross, Mike Jerrick, Michael Klein), politics (Vince Fumo, Risa Vetri Ferman), business (Wayne Kimmel, Drew Milstein, John Westrum), sports (Shane Victorino, Pat Croce), real estate (Allan Domb, Ori Feibush), the Rittenhouse social whirl (Sabrina Tamburino Thorne, Maria Papadakis, Beka and Jesse Rendell), the Main Line social whirl (Maripeg Bruder, Babs Snyder), and the social whirl of infamy (Chuck Peruto, Susan Tabas Tepper). They also include six Hamiltons, three Binswangers, three Tinaris, two women with the first name of Princess, and New York City socialite Dini von Mueffling. (“She represents a company that sells a communication service to arenas,” Garrett explains when I ask how he knows her. “She also represents Monica Lewinsky.”) In a nutshell, Garrett Getlin Snider is friends with everyone who’s ever been photographed by HughE Dillon. And, of course, with HughE Dillon.

Susanna Foo? John Westrum? Vince Fumo?

“I used to worry about it, and wonder about it, in a way,” Lindy Snider says of the adult social network Garrett began building before adolescence. “Not that it wasn’t okay, but it was interesting to me that these were the types of people he would gravitate toward. My [second] husband and I would say, ‘Wow, maybe he should be spending time with kids his own age.’ But he was thriving in this world that he himself had created.”

“I’m still concerned, as a father,” says his dad, Scott Getlin, an actor/singer/songwriter now living in Nashville. “I don’t know who his posse is, you know what I mean? I want to see him with some friends, and sometimes I get worried because he’s always with elderly ladies or whatever with the things that he does. And I think that’s great, but you know, I would love to see him with some friends his own age he can relate to. But hey — it is what it is.”

TO TRY TO understand Garrett Snider, you have to start at the base of the family tree. That’s Ed. The son of the owner of a string of grocery stores, Ed Snider built a sports dynasty by becoming a minority stakeholder in the Eagles, then the owner of both the Flyers and the 76ers. He also became a prominent philanthropist, establishing his own youth hockey foundation and sitting on various boards.

Ed has led a colorful life, dutifully recorded by the city’s Stu Bykofskys, replete with four marriages, two sets of kids, family feuds, messy divorces, a Kennedy Compound-type Maine enclave, and vacations to the islands for the entire brood. He appears to be a formidable paterfamilias, more J.R. Ewing than Lord Grantham. Over the years he’s earned a reputation as a ferocious deal-maker and business tactician, which is probably not unrelated to his co-founding of the Irvine, California-based Ayn Rand Institute in 1985.

“He is quite unique,” Ed says of Garrett, “in the fact that as young as he still is, he does all of these things charitably. It’s always been a great interest of his. I think it’s fascinating that a young man would be that involved.”

In the past year, Garrett has done two things that have attracted notice, particularly inside the family. He left his freshman semester at the University of Maryland — Ed’s alma mater — to transfer to Drexel. (“Look, everybody has to pick their own path,” Ed says when I ask if he was disappointed.) Just a few months earlier, Garrett had legally changed his name, which had more than one observer clucking that he was trying to elbow his way to a bigger inheritance through callous rebranding. “Everybody wants Ed’s attention and his perks and his money,” sniffs one charity-circuit vet who rotates through the Sniders’ social orbit. “Garrett tries to pass himself more as one of Ed’s kids than his grandkid.”

But he’s not Ed’s kid; he’s Lindy Snider and Scott Getlin’s kid, and there is little doubt that the tug of war between them during and after their bitter, bare-knuckle divorce, which began when Garrett was still a preschooler, affected him deeply. “I was not shielded from the fact our situation was strained,” Garrett says. “I had to face the reality of that. Dad’s not here, Mom’s stressed, my sisters are young. It’s hard. Because when you’re young, and your dad isn’t home and doesn’t live near you, you think he doesn’t love you. For the longest time it was very black-and-white to me. He’d call or visit, and if he didn’t, he didn’t.”

When I read that quote back to Scott Getlin, he seems genuinely torn up. “It broke my heart,” he says of hearing of the surname switch, which he says “is for one reason only” and caused him and his son not to speak for months. Garrett maintains that he changed his last name because it’s also his mother’s, and because the Sniders are, in fact, his de facto brood. Scott Getlin contends that he was out-dazzled by the glamour and wealth of la famiglia Snider: “You live in a huge mansion and you’ve got a lake house and four boats and this, that and the other, and then when your dad comes, it’s like, ‘Oh, what am I going to do with him?’” he says. “It was always like, Yeeesh, I can’t compete with that.”

R.C. Atlee, a 30-year-old realtor for high-end Main Line estates whose family blood runs the proper shade of blue, was also a precocious young man who flitted through Philadelphia high society at a young age, so he understands, perhaps better than most, what it’s like to be Garrett. He says the real issue isn’t that Garrett wants the spotlight, but that so many of the youngest generation of what might be called the city’s “first families” on par with the Sniders — the Perelmans, the Kellys, the Hamiltons — seem to have little interest in the families’ legacies. “There is always this question of who wants the scepter,” he says. “And often it seems to me, from my personal experience with these families and growing up with their kids, nobody does. There is not necessarily a lot of interest in ascending to the role of most photographed person in the family, or most visible person in the family. A lot of these kids can’t wait to go to college in a town where nobody knows who their parents are and get a nice job somewhere where they can relate to the world in a different way. There are others who seem to really love the social life, and love the community, and they really value not only the role and the importance that their family has, but also the possible role that they can play in making an impact or making change. That’s Garrett.”

“When you stick your head above the parapet, people will shoot,” Garrett says when I ask him about those who believe he’s only interested in having his picture taken. “And I’ve prepared myself for that since I’ve tried to do anything beyond the expectation. If that’s what people think, oh well.” I ask him if he cares what people think. For the first time in all of our hours together, Garrett Getlin Snider gives me a one-word answer: “No.”

GARRETT GREW UP inside the Wells Fargo Center, and knows it like a young man would know his childhood playground. One night before a Flyers game, we walk through the bowels of the arena (Garrett doesn’t actually watch the games — he’s too busy kibitzing), and he introduces me to what seem to be dozens of people, from VIPs to ticket takers. Everyone knows him. As we leave, I remark to him how amazing that is. “I just call everybody Joe or Lou,” he says, shrugging. “If it’s not right, it’s probably close.”

Because what’s most important to Garrett is for all these people to feel that he remembers them, that he cares. “He’s precocious and very mature,” says Richard Vague. “He has a kind of wisdom about human nature and relationships.”

What he doesn’t have is life experience. And sometimes there’s no substitute for that, no matter how many HughE photos you smile for. For every boldface name who puts an arm around him and thinks he’s swell, there’s another who might be cozying up to gain entrée into the Sniders’ world of power and influence. “I definitely worry about that,” Lindy Snider says. “Sometimes people’s motives are not as pure as his.”

But does living in this world carry a social cost as well? Not one person I spoke to could recall ever meeting a girlfriend or a date of Garrett’s, or him having a romantic life in high school or thus far in college. Considering his light voice, impeccable grooming and wide circle of Dini von Muefflings, it’s understandable that people assume he’s gay, and that he’s staying in the Snider walk-in closet so as not to alienate his politically conservative grandfather — a man who once invited Sarah Palin to drop the puck during a Flyers game.

Ridiculous, Garrett counters, insisting that he dates girls, but that if he were gay it would be a complete “non-issue in the family.” “I acknowledge that my life is unconventional. It’s a lot for people to digest,” he says. As for the gay rumor, he says, “It’s a concept for people on the outside looking in. I think it’s a quick, easy way for people to make sense of who I am and the way I live.”

A week later, we’re standing in the parking lot of the Mission Kids Child Advocacy Center in East Norriton. Of all of Garrett’s causes, this is the one closest to his heart. Instead of having to repeat — and repeat — their painful stories to detectives and lawyers at a police station, children who have been physically or sexually abused can come here to tell all the details once, to a forensic interviewer trained for that kind of emotionally wrenching work. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think the place, tucked inside a nondescript office building, is a daycare center. The result of a crusade by former Montgomery County district attorney Risa Vetri Ferman to better protect the littlest victims, Mission Kids, in its six years, has helped more than 2,500 children get past the wounds of their ordeals, and helped put away sex offenders in the process. Garrett started volunteering here at the age of 15.

Today he’s dressed in his standard uniform: gray pullover, vest, jeans and expensive driving slippers. He’s once again talking about the kids who suffer, who need someone. I point out that he experienced his own brand of pain growing up — and perhaps lost his childhood in the process. I wonder, out loud, if he’s buried his pain in all of this. We end up talking about his relationship with his dad, which he circumspectly describes as “cordial.” He admits he was angry with his father for a long time for letting their relationship dissolve. “But as I got older, I realized we are all just trying to be happy,” he says. “So whenever I go to judge his failure and his whatever you want to call it — his inability — [I realize] that he is trying to feel good, and it’s harder for him to do that than it is for me. So I take what I can get, and we have a happy relationship on my terms. I know what the limitations are.”

He also knows — and feels, deeply — the limitations placed on the kids he’s trying to aid. “The common denominator of the charities that interest me is that they help kids with little or no resources who are under physical or emotional attack,” he says. “You cannot live a happy life when you are underwater like that.”

There are people who wonder if Garrett Getlin Snider himself is underwater — about the young man who never got to be a child. They kiss him and hug him and perpetuate his identity as the Best Boy in the World, even as they privately shake their heads and muse about how it’s all going to turn out — if there will be a day of reckoning when Garrett looks in the mirror and wonders why he spent all of his time fretting about every kid except the one staring back.

For now, he’s studying communications at Drexel, a path his mother hopes will lead to a career in politics or journalism. He seems wan about potentially working in the family business. (“I like hockey,” he says in the passing way you might say you like to watch TV.) Instead, Garrett sees a future built on what he’s already doing: helping kids. He’s raised money for his grandfather’s foundation, but, he points out, you have to be 25 to be on its board. You sense it’s not a coincidence that he’s aware of that.

You also sense that, perhaps ironically, Scott Getlin thinks about Garrett’s future — and his happiness — on a deeper emotional level than anyone else in his life. “Garrett has a lot of layers to him, and he is not an emotive person,” Getlin says. “You know, he keeps his cards close to the vest. And sometimes I’ll catch him and I’ll see he is carrying a burden. My wish for him is that he’ll become free. Just free in his heart with whoever he is, and whatever he is, and just to be free and be happy.”

Garrett insists he’s already there. “I honestly believe — and this may sound obnoxious, but I have worked very hard to feel this way — I honestly believe I am the happiest person I know,” he says. “That’s the God’s honest truth.”

Published as “Garrett Getlin Snider Is Not Your Average Teenager” in the January 2016 issue of Philadelphia magazine.